Was it the sound of Theodor Herzl's gavel that set the delegates' hearts racing at the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel in December 1901? Or was it because of Yona (Johann) Kremenetzky's tears that the die was cast – leading to the establishment of the National Institution that was to become the executive arm of the Zionist Organization? Congress delegates burst into thunderous applause as the vote was announced for the founding of Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael-Jewish National Fund (KKL–JNF). It was a momentous occasion, and the delegates knew it. It was the moment that Zionism actually set foot in Erez Israel – not by mere words, declarations, debates, and resolutions, but by land reclamation via a national fund of and on behalf of the Jewish People.

Theodor Herzl's voice resounded through the hall of the Basle Casino, where the Fifth Zionist Congress had convened. He said that the time had come to implement the plan for a national fund. "The people," he said, "will forever be not only the donors, but also the owners of this dedicated capital." When Herzl stepped down from the podium, one or another of the representatives of the Jewish People rose to speak for or against the proposal. After four days of deliberations, there was a sense of urgency in the air: the making or breaking of a crucial – the most crucial, perhaps – endeavor to restore the Jewish People to its homeland.

One of the delegates, Dr. Schalit, explained that the fund would be "the eternal possession of the Jewish People. Its monies would be used solely for the purpose of land purchase." To many people it was clear that, whereas the Congress spoke Zionism, a fund could practice Zionism: broadly supported, it "could be an important instrument of the practical work," as another delegate said.

Yet another delegate cited Professor Zvi Hermann Schapira's vision for a national fund to reclaim the soil of Israel. "Schapira," noted this delegate from Poland, "said that once the idea of a national fund were realized, he would be able to die in peace. I say the opposite: once an abiding [kayemeth] national fund [keren] is realized, I will be able to live in peace."

Schapira, who passed away shortly before the Second Zionist Congress convened in 1898, never knew that four years later his proposal would figure prominently in a drama that was to be remembered as one of the high points of the Congresses. It was a moment when all eyes again turned eastward, to Erez Israel, and a day when Zionism in the diaspora reconnected with a land that was far from the body, but close to the heart.

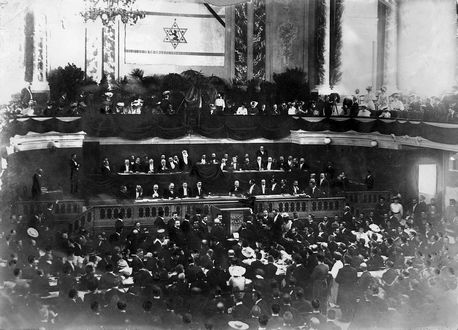

First Zionist Congress in Basle, 1897. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

While Schapira's proposal had many advocates, it had also one critic, jurist Max Bodenheimer, who insisted on a precise legal formulation of the fund's goals prior to approval. For this reason, the voting on the fund's establishment had been postponed from one Congress to another. And even on that cold winter day in 1901, there were those who again suggested putting off the vote because the charter stipulating its powers had not yet been fully set down. With a majority of 81 to 54, Bodenheimer had again succeeded in pushing through a resolution to defer the vote on the fund's establishment to the next Congress.

Theodor Herzl had not been present in the hall when the resolution was adopted, and one of the delegates rushed off to inform him of what had happened. Finding him in the lobby of the building, he had also told Herzl that Vienna delegate Yona Kremenetzky, who had championed the ratification of the fund's establishment, had broken down in tears upon hearing that the decision had again been delayed.

Herzl, who saw the land of Israel reflected in Kremenetzky's tears, had hurried back to the hall. There, his loyal aide and deputy, David Wolffsohn, who was to become the second president of the Zionist Organization, suggested a way out of the predicament: a revote, divided into two parts. First, Congress delegates would vote on the question in principle of whether or not a fund should be formed. Only afterwards, would they discuss its functions. Herzl pressed Congress participants for a decision "so that we do not disperse again, having accomplished nothing, after years of exploring the possibility of establishing a national fund." Turning to the delegates of the Fifth Congress, he had issued an impassioned plea: "We do not wish to disperse yet again without creating this apparatus!"

Lengthy discussion followed. Finally, he had demanded of the Congress, "Do you want us to start a national fund immediately, yes or no?" Many were the voices in the audience that answered in the affirmative. He continued: "Yours is the power to decide whether to postpone the establishment of the fund for another two years or until the coming of the Messiah!" And from all corners of the hall came a roaring chorus of "No! No!" Gratified by the reaction, Herzl had put to the vote a proposal that "the fund will be the property of the entire Jewish People." Congress delegates cast their ballots. A hush fell over the hall: as if here, at this moment, the fate of the land of Israel and the Zionist Movement hung on the scales. When Herzl announced the results – 105 in favor and 82 opposed – stormy applause rocked the hall. At 7:40 p.m. on December 29, 1901, 19 Tevet 5638 according to the Hebrew calendar, Herzl proclaimed: "The Jewish National Fund has been created." Thus, this date became the anniversary and festival of Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael-Jewish National Fund (KKL-JNF).

By a strange coincidence, the date already was a festival in Eretz Yisrael. On that same day, in 1878, the first furrow had been plowed at the farming colony of Petah Tikva. So that First Furrow Day became also KKL-JNF Day. The same day, separated by an interval of 23 years – and the same festival, the festival of the land of Israel.

After the close of the First Zionist Congress, Herzl had written in his diary that in Basle he had created the Jewish state. Four years later, in the same city, Herzl created KKL-JNF, which, fifty years later, would largely determine the borders of the state he had foreseen.

The proposal to establish a national, popular fund of far-reaching vision had been raised back at the First Zionist Congress by Zvi Hermann Schapira, a mathematics professor at Germany's Heidelberg University. Its purpose: to purchase land in Palestine. The Congress had welcomed the plan with enthusiasm, resolving that there was "a special need to establish a national fund and a Jewish bank." And it had charged the Zionist Executive with drafting a detailed proposal for discussion at the following Congress. Herzl, too, had been excited by Schapira's motion, though in no rush to raise the subject at the successive Congresses; perhaps because he had hoped first to receive a charter from the Turkish Sultan for the establishment of a Jewish state. In his eyes, the political initiatives to this end took precedence over a fund. He believed that only after he had acquired a charter, and the Jews began to immigrate to Erez Israel, would there be a need for a fund of a "general-national character," as Schapira had put it, to purchase land.

But in the winter of 1901, upon the convening of the Fifth Zionist Congress, the charter that Herzl dreamt of seemed all too remote. Consequently, Yona Kremenetzky, an industrialist and electrical engineer, decided to urge Herzl and the leaders of the new Zionist Movement to create a fund that would restore the land to the ownership of the Jewish People, regardless of any political measures. Kremenetzky, who saw the land of Israel in his mind's eye, knew that the surest road to reach it was not through international politics, but through the heart of the Jewish People and its yearning for its land.

Delegates to the Fifth Zionist Congress. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

Now that the Congress had ratified the Fund's formation, an ecstatic Kremenetzky announced that he was making a contribution of £10 – the first contribution registered to the Fund's credit. Herzl was quick to follow suit, announcing his own contribution, and instantly matched by David Wolffsohn. All at once, after the historic decision to establish the Fund, delegates from various countries, many of whom had only seconds before voted against its establishment, now came up to the platform to pledge their contributions. These contributions were to be inscribed on the first page of the first volume of the Fund's Golden Book.

At another session of the Fifth Zionist Congress, Kremenetzky was elected Fund Chairman. He, who had been so adamant about realizing Schapira's vision, was widely perceived by Congress members as the right man for the job. A month later he set up the head office in Vienna and began to think of ways to implant the Fund in Zionist hearts. It was clear to him that KKL-JNF, as it had been defined, could carry out its mission only through donations from the Jewish People and, for this purpose, he suggested three unique undertakings that have remained a part of the Fund ever since.

He initiated the Golden Book, in which, he suggested, the name/s of honoree/s and/or donor/s be inscribed for donations for land purchases in Erez Israel, to be made on special occasions. The inscription fee for the Golden Book would, he believed, be a symbolic expression of personal participation in the Zionist enterprise. The inscription and donation would be both a gift and an honor.

At the same time, he hit on another idea, one that would convey the Fund's symbols and scenes to the entire Jewish world. In a local print shop in Vienna, he had KKL-JNF stamps printed. These would be used on official documents of the Zionist Institutions, and on the correspondence of Jewish communities of the First Aliya immigration wave in Erez Israel, constituting an additional avenue for KKL-JNF to raise funds for its activities.

The first stamp, the Zion Stamp, was produced in 30 million facsimiles and distributed throughout the Jewish world. Many people put it on their letters next to the official, national stamps of their countries. The sums collected from stamp sales were not large, because of their low face value (equivalent to the least expensive stamp in the country of distribution). But Kremenetzky saw this as an effective means of bringing KKL-JNF closer to the Jewish People, who were both the Fund's owner and donor. In his eyes the stamps were a valuable public relations tool and a collectors item, and would refocus Jewish hearts on the pictured landscapes, drawing them to Zionist symbols.

This is how KKL-JNF's first Chairman embarked on both fund-raising and the extensive educational activities that linked the diaspora with the far-away soil of the land of Israel. Kremenetzky believed that a small picture or symbol, traversing continents and reaching across great distances, would transmit to every corner of the world the fact of the Fund's existence and the goal that it strove for: The land of Israel. Scenes of Erez Israel were always on Kremenetzky's desk and, with every educational or organizational step that he initiated, he felt as if he were coming nearer and nearer to those gray, cold, static pictures and injecting the Zionist Movement into them.

Kremenetzky inaugurated also another device to encourage contributions from every Jewish community. He adopted an idea suggested by Haim Kleinman, a bank clerk from Eastern Galicia, to place, in every Jewish home, a collection box, similar to the well-known charity box of Rabbi Meir Baal HaNess (the Miracle Worker). Kremenetzky soon had a small box made at a local metal factory, inscribed with the words "National Fund." Because of its color, it became known as the Blue Box. The factory produced hundreds of boxes, which he distributed to almost all the communities in Europe, wherever there were Jews. Again, it was clear to him that donations from the Blue Box would account for only a small part of the Fund's budget. But their great importance lay in their contribution to Zionist education and to bonding diaspora Jewry with the land of Israel.

To encourage larger donations, Kremenetzky suggested that every donation be publicized in Die Welt, the official organ of the Zionist Movement. For years the donor lists were a regular feature of the newspaper, which enjoyed a wide readership among Zionists in Europe. Contributions large and small in those first years proved how efficient Kremenetzky's fund-raising techniques were and how much they infused Jewish hearts with love for the homeland. Fund stamps brought the soil and vistas of Erez Israel to diaspora eyes, and Jewish children became familiar with the map of the land and its settlement points thanks to the sketches on the Blue Box.

Chemistry lesson in HaGymnasia HaIvrit in Jerusalem, 1923. The school was on KKL-JNF purchased land in Bukhara Quarter and later in Rehavia. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

In April 1902, Menahem Ussishkin, one of the leaders of the Hibbat Zion (Love of Zion) Movement in Russia, wrote in a manifesto to the Zionists of eastern Europe: "I summon you, brothers, to a difficult and trying task, but one of great and noble purpose – the redemption of the land of Israel for the People of Israel." A month later, he dispatched another manifesto, "No opportunity is to be missed – no gathering, no social get-together, no party, no celebration or gala – to collect money and gain support for Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael."

Twenty years later Ussishkin was to become Fund Chairman and, in his two decades in office, initiate KKL-JNF's sizable land purchases. Meanwhile, during the Fund's first year, Kremenetzky was gratified to learn that the Fund had gained not only monies for the purchase of land, but also actual title to a tract in Erez Israel. Yitzhak Leib Goldberg, another Hibbat Zion leader in Russia, had transferred to KKL-JNF 200 dunams in Hadera. Years later an additional contribution from Goldberg made possible the acquisition of land on Mt. Scopus in Jerusalem, where the Hebrew University was to rise.

Many of the delegates who voted for the Fund's establishment at the Fifth Zionist Congress hoped that at the following Congress, the Sixth, they would finalize the Articles of Association and decide on the immediate purchase of land in Erez Israel. But discussions at the Sixth Congress were dominated by Herzl's motion to declare Uganda a temporary haven, which, in fact, almost split the movement.

To the relief of the opponents of Herzl's Uganda plan, the Congress resolved not only to explore the Uganda settlement option, but to establish an Erez Israel Committee which would simultaneously aim at practical work in the land. At the same session, Kremenetzky expounded the need "for all ranks of the Jewish People to unite in the Fund's work," and succeeded in pushing through a resolution to allow KKL-JNF to start buying land in Erez Israel without waiting for its seed capital to reach £200 thousand.

In 1904, three years after the Fund was established to redeem the soil of Erez Israel, it registered the lands of Kfar Hittim in Lower Galilee as its first land purchase. In the Zionist Movement, the transaction became known as the first purchase because the Fund bought the land, but did not redeem it; Kfar Hittim had already been "redeemed" into Jewish hands by Haim Kalvaryski of the Anglo-Palestine Company, which transferred it to KKL-JNF. Herzl, who was kept abreast of this first transaction, visualized the Jewish colony that would rise on the soil and the first kernel of settlement of the Jewish state.

That year, too, the first 2,000 dunams were purchased at Hulda and the first 1,600 at Beit ‘Arif (east of Lod), which was soon renamed Ben Shemen. This redemptive act, the first in the history of KKL-JNF, was sealed at a cost of 20 francs per dunam and in the name of a proxy, David Zalman Levontin of Rishon LeZion, because the Fund was not yet a legal entity.

Also purchased and transferred to KKL-JNF were lands in Daleiqa and Umm-Juni near Lake Kinneret (the Sea of Galilee), through the offices of Yehoshua Hankin, the man who for the next forty years would purchase hundreds of thousands of dunams for the Fund.

In those days of first land purchases, Menahem Ussishkin published a document asking for assistance to the Fund in its budding redemptive activity. He called on the delegates of the Seventh Zionist Congress not to rest content with "political work" in Constantinople, but to immediately embark on "practical work" in the land of Israel in order to obtain the charter for the establishment of a Jewish state "from both above and below." In his document, which he entitled "Our Zionist Program", he voiced a demand to nationalize the land. This, he believed, "can be implemented only through Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael-Jewish National Fund…"

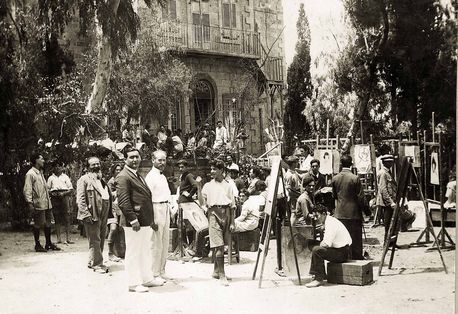

Bezalel School of Art and Design, purchased by KKL-JNF. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

Although the leaders of the Zionist Movement viewed the Fund as an instrument for acquiring land for agricultural-Zionist settlement in Erez Israel, in 1905 – a little more than a year after the initial acquisitions – KKL-JNF was already assisting in the purchase of land and buildings not only for rural settlement, but for education purposes in Jerusalem. Instead of virgin land, where buyers dreamt of raising wheat fields or blossoming orchards, the Fund bought two large "manors." The premises, on a hill in new western Jerusalem outside the Old City walls, were slated for the cultivation of arts and crafts at the Bezalel School of Art and Design.

In 1906 the Fund made loans totaling 250 thousand francs to build the Ahuzat Bayit quarter outside of Jaffa, the nucleus around which the first Hebrew city of Tel Aviv was to rise. Sixty out of the first 66 inhabitants of Tel Aviv built their homes with the help of KKL-JNF. The Fund's loans also financed the construction of the neighborhood of Hadar HaCarmel in Haifa.

That same year the Kiryat Sefer Agricultural School was founded at Ben Shemen for the orphans from the Kishinev pogroms. Although the facility did not last long, it marked another step on the road of KKL-JNF activities: redeeming the land was not enough – the land had to be held, even if, at the outset, the investment appeared to be economically unjustified. Indeed, years later, one of the Fund veterans confirmed that the idea was to hold on to every piece of land and use it for every possible Zionist enterprise – agricultural or urban, rural or educational. The Fund's land-buyers envisioned not only fruit and harvests, but people – adhering to the land and deepening their roots in it in any way they could.

At KKL-JNF's head office in Vienna the staff had begun to mark off land purchases on the map, point by point. According to the principles ratified at the Sixth Zionist Congress, the Fund was not only obliged to purchase in Erez Israel land for construction, fields, and orchards, as well as forests and tracts of all kinds, but also to cultivate the purchased lands, or transfer them for cultivation, or lease them to Jews with a prohibition against sub-leasing. It was also required to create or support various projects to serve this goal.

To this end, the Fund financed a research expedition to study plant life and soil quality in the Jericho Valley, the Dead Sea, and Upper Galilee. This first expedition, headed by German biologist Max Blankenhorn, was joined by Zichron Yaacov botanist Aaron Aaronsohn. On one of the expeditions in the north, Aaronsohn discovered an early form of wild wheat, Emmer. As a result of this discovery, he was able to raise funds in the U.S. for the establishment of an agricultural research station and, in 1910, KKL-JNF supplied the funds to purchase land for the station in Atlit, and supported its functioning.

From his office in Vienna, Kremenetzky worked not only to purchase land but to realize another of his dreams: the afforestation of Erez Israel. "We must establish a national forestry society for the planting of trees in the land," he said to Herzl as soon as he read the latter's The Jewish State. According to his proposal, every Jew would donate one tree, a few trees – even ten million trees! Herzl himself was caught up by the idea, but little did he imagine that the first forest soon to be planted by KKL-JNF would be to his memory: Herzl Forest.

KKL-JNF, while Herzl was still alive, had taken over the management of a fund for the planting of olive trees, established on the recommendation of agronomist Zelig Suskin. Since olive trees bear fruit within five years of planting, Suskin envisioned both a venture with speedy returns and a symbol of the hold on the land. The olive tree, he said, "lives longer than any other fruit tree." Thus, the first planting in the land of Israel would be an act that spanned generations.

By KKL-JNF calculations, the yield from the olive trees could have funded the maintenance of a university in Erez Israel – "idealistic work for idealistic assets." Also botanist Otto Warburg suggested planting olive trees at the time in order to export olive oil to the diaspora as a symbol of the achievements of the Zionism reborn. The site chosen for the olive groves was the lands of Hulda, already owned by KKL-JNF and having a running workers farm. They were to be named for Theodor Herzl, founder and leader of the Zionist Movement, who died in 1904, at the mere age of 44.

A year after Kremenetzky ended his term as KKL-JNF Chairman, he learned that his dream had been fulfilled, shades of green having been imprinted on the first lands that the Fund had redeemed. Although only a quarter of the 12,000 olive saplings took root, the forest survived, but a few years later on the advice of experts inedible-fruit trees were planted. And so it was that a 250-dunam grove of olive trees and pines was planted at Hulda, marking KKL-JNF's first afforestation project. In fact, during the early years, one of the planters could still single out from the green the very first tree planted by KKL-JNF in its very first forest in Eretz Yisrael.

In 1907 KKL-JNF offices moved from Vienna to Cologne in Germany, ending the "Viennese Period" in Fund history. At the Eighth Zionist Congress there was a heated debate between those who demanded "conditions to create" and those who demanded "that conditions be created" to attain the political goal of a Jewish state through practical work in Eretz Yisrael; the latter won the day. The Congress chose Max Bodenheimer – the man who had tried several times to postpone the vote on the establishment of the Fund – as Chairman of KKL-JNF, and decided to establish a Palestine Office through which KKL-JNF would administer the work of settling the land.

The future land purchases and projects of the Fund, which financed the lion's share of the Palestine Office budget, were coordinated from the two rooms that Office Director Dr. Arthur Ruppin rented on Butrus Street in Jaffa. At the encouragement of Dr. Ruppin and his assistant, Dr. Yaacov Thon, the immigrants of the Second Aliya arrived to settle those first lands purchased by the Fund.

Hadar neigborhood in Haifa, built on KKL-JNF lands. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

It soon became plain to the Fund directors at the Head Office and in the Palestine Office that it was not enough to purchase lands; there was an immediate need to reclaim and till the soil. Although the Fund had been established to redeem lands – it was now clear that "redemption" meant not only title registration and deed transfer (by Turkish kushan), but clearing rocks, plowing, planting, and settling on the land. The Fund therefore remained actively involved in the lengthy processes of purchasing, reclaiming and cultivating land right up to the stage that settlement groups were organized and new settlement forms took shape.

In the space of six years, since its establishment to redeem the soil of Erez Israel, the Fund had also become the key settlement agent during the Second Aliya period. It saw itself as partner to both every Zionist settlement enterprise in Erez Israel and every educational project of the Zionist Institutions. Following the decision of the Zionist Congress to found a high school in Jaffa, KKL–JNF contributed a tract of land on Ahad Haam St. Tel Aviv for the Gymnasia Herzliya high school, built in 1910. It also helped erect another high school, HaGymnasia HaIvrit, in Jerusalem, which was initially housed in the Bukharan quarter, as well as the Re'ali High School in Haifa and the Tahkemoni Religious Zionist School in Tel Aviv. The Fund directors well understood the meaning of the Hebrew saying that "there is no Torah without flour"; education, in all its streams, required land for schools. This, too, was part of the redemption of Erez Israel: every Zionist enterprise needed land. Moreover, land unused was virtually unredeemed.

To settle the lands redeemed and to assist every type of settlement, the Fund also allocated a tract of land that it purchased near Petah Tikva for its first workers colony and, in 1908, the moshava of Ein Ganim rose on it, which was like a cooperative farm.

On the lands of Daleiqa near the Sea of Galilee, which had stood desolate, the Kinneret Women's Farm was established and, in 1909, on the lands of Umm Juni, a small kvutza – the forerunner of kibbutz – was created: Deganya soon earned the title of "Mother of Kvutzot." Ruppin was happy to report to the head office in Cologne that, "we have succeeded in establishing a collective community at Kinneret. We have erected a hut at Umm Juni…" Years later he related that in those early days, as the first decade of the Twentieth Century drew to a close, he had not appreciated that "the act being performed here was to become acclaimed for its importance to the development of settlement in the land." But his heart had told him "that humble beginnings could have mighty consequences."

By the end of its first decade, Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael-Jewish National Fund was both owner and settlement agent of the lands it had redeemed, it had planted its first forest and assisted Zionist education. All these endeavors would continue to be part and parcel of the Fund over the coming decades, furthering every possible project in the land of Israel.