Despite the clear KKL-JNF policy set down at the 1920 London Conference, and the fact that the hundreds of Third Aliya immigration pioneers required land on which to establish kibbutzim and kvutzot, Fund Chairman Nehemia de Lieme demanded that land purchase and settlement be limited, and expenditure curbed. There was no question of his having the land's best interests at heart, but as a banker, De Lieme insisted on prudent budget management.

At the very same time, Yehoshua Hankin returned from a brief spell in Turkish exile and once again, set out for the Jezreel Valley and its landowners in yet another attempt – one of many numerous trips and persuasive sessions – to acquire its eastern lands. Defying all business sense, he travelled to Haifa to meet with a representative of Beirut's Sursuk family, who owned the Valley lands. He had not a penny in his pocket, nor authorization from the Zionist Institutions; but his bones ached for the land. He was well acquainted with the landowners and, after 20 years of convoluted negotiations, he knew that that he could not let a single opportunity go by.

KKL-JNF's Executive in Erez Israel – Menahem Ussishkin, Akiva Ettinger, and Arthur Ruppin – decided to buy the Valley lands which Hankin had labored to obtain, without approval from the Board of Directors in the Hague. The Hague Chairman, de Lieme, headed a committee visit to Palestine to assess the Fund's needs and activities, and to tour the Valley. But on October 15, 1920, two days before the committee's arrival, Hankin signed a contract to purchase 50,000 dunams in the Valley. Ussishkin, as he wrote in his memoirs, had told them outright: "We did it in order to settle the affair before you came, so that you would not be able to interfere…"

The committee in fact did advise decreasing the number of land transactions in Palestine, although it authorized Hankin's Valley purchase retroactively. De Lieme exercised his right of veto to oppose the purchase, and was overruled by the Zionist Executive – removing all threat to the transaction. Ussishkin and colleagues could breathe easy. "The struggle for the Valley" was over. Twice as large as the sum total of KKL-JNF's other lands at the time, the new assets, together with other purchases at Kiryat Anavim and elsewhere in Judea, in a single year tripled the Fund's holdings to 65,384 dunams.

The Jezreel Valley purchase, the Fund's largest, led both to de Lieme's resignation in the summer of 1921, two years after having assumed the Chairmanship, and to sharp debate at the Twelfth Zionist Congress convening in Carlsbad that autumn.

Countering de Lieme's attack on the Valley purchase, Ruppin, the Director of the Palestine Office who had supplied the money for the deal, responded that he and his colleagues would have been derelict in their duties if they had not authorized the transaction. Menahem Ussishkin, popularly known as "the iron man," delivered a fiery speech in which he noted that the land was indeed costly, but in Erez Israel, time was even costlier: "If the choice is between buying dearly today or cheaply tomorrow, I choose today!" he said. "And if the land is expensive, you can say that Ussishkin and Ruppin are terrible businessmen. But had we missed the opportunity for purchase, you would have been entitled to regard us as criminals." Summing up, he added: "Throw me out of the leadership, but the Valley will remain ours." And, he added, while no one doubted de Lieme's Zionist ardor, "if the choice is between breaking faith with de Lieme or with our portion of Erez Israel – I choose de Lieme, and I believe that everyone will agree with me."

Ultimately, all the delegates did agree with him and the land purchase was approved to thunderous applause. It seemed to them that the hands they raised in vote propelled Zionism deeper into Erez Israel, especially into that promising region that had been so far away.

A few months later Ussishkin was appointed KKL-JNF's fourth Chairman, and the Head Office moved from its fourth seat in London to its permanent headquarters in Jerusalem. The move from the diaspora to the homeland took about a year. But, once it was completed, the Fund began to manage its redemptive work in Erez Israel from the soil of Erez Israel. In the two decades that followed, Ussishkin steered the Fund towards its largest land purchases since its inception.

Shortly before the move to Jerusalem, the Fund's General Assembly meeting in Prague decided that hereafter in the Articles, it would be known solely as Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael; this was to be its only official name.

While Ussishkin regarded land redemption as Zionism's most important act, he believed that the Fund should purchase only agricultural land, and refrain from urban acquisitions: "Our main goal is to revert our People to farmers." His supporters agreed, "…our People on the whole are strangers to farming and lack the inner resources to bring about so great a revolution…if conditions are not found to facilitate agricultural settlement, they will simply make their way to the towns…"

Opponents, however, claimed that it was the Fund's duty to buy up all land, including urban areas, in order to channel settlement to the towns as well and to prevent speculation. They cited the Chairman's own fondness for the tune, "A dunam here, a dunam there," saying that it made no difference what type of land was redeemed in Erez Israel – so long as it was redeemed.

In the end, it was decided to purchase also urban land. In southern Jerusalem, a large tract of land was bought and the neighborhood of Makor Haim was built. Near Tel Aviv, the Fund acquired land for a Jewish neighborhood for residents forced to move out of Jaffa after the Arab riots of 1921. The Nordiya neighborhood rose here, named after Zionist leader Max Nordau. Nearly 300 dunams were procured next to the first Hebrew city of Tel Aviv to house laborers and craftsmen, and the Borochov quarter was built, named for Dov (Ber) Borochov, guru of Poalei Zion (Labor Zionism). In Haifa, 66 dunams were obtained on the slopes of Mt. Carmel for the construction of an urban neighborhood. Initially known as the Yehiel Quarter, after Dr. Yehiel Czelnow, a leader of Russian Zionism and the World Zionist Organization, it is today the heart of Haifa's Hadar HaCarmel. Again in Jerusalem, the Fund also purchased land in Rehavia, where the National Institutions, including KKL-JNF, built their head offices, and the HaGymnasia HaIvrit high school was erected.

During this decade, the Fund undertook extensive amelioration of the lands it had redeemed, defraying all the costs of reclamation, including the wide-ranging drainage of swamps. Much – if not a wild – imagination was needed at times to even envision the many-hued landscape of cultivated fields that would replace foul, malaria-breeding water. To give life to the imagination, life had to be given to the soil as well, with hoe and pitchfork. Stagnant water had to be drained and clear water ducted to the Valley. Guiding the Fund's toil and labor was the call sounded by a delegate at the Thirteenth Zionist Congress in Carlsbad: "Keren Kayemeth must never hand over malaria-ridden land to pioneers."

The drainage of the Valley swamps began in 1922 on a scale of work unprecedented in Erez Israel. In the eastern part of the Valley, 16,000 dunams were drained and 35,000 restored in 50,000 man-day units of work. Mosquito-breeding nests were stamped out, the festering bogs turned into blossoming land and, like cinematography, yellowing frames of landscape gave way to color – white houses, red roofs, green fields. Fancy took flight and even the building of a port was suggested for the Valley – there was certainly no lack of water… Water, however, had begun to flow through pipes and sprinklers and the Valley became the breadbasket of the pre-state Jewish community in Erez Israel.

Tractor in the Jezreel Valley. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

Zionist engineer Pinhas Rutenberg, founder and director of the Electric Company, who was known as "the old man of Naharyim" because of the facility's location, made a precise survey of the area for the building of a road to join up the Jezreel Valley with the Haifa-Nazareth road. And soon, poet Abraham Shlonsky could write, "sail trimmings have spread through the Valley"; the white tents – and then huts – of Nahalal.

At KKL-JNF, now headquartered in Jerusalem – first in a rented building in the Greek Colony, then on Luntz St. and, finally, at its permanent seat in the National Institutions compound in Rehavia – three figures stood out. All were to be integrally involved in the Fund's work for years to come, helping Ussishkin buy up more and more land, adding more and more pegs to the Head Office map.

The first was Ettinger, an agronomist and the Director of Land and Afforestation, who examined the type and quality of the soils offered for sale to the Fund. The second was Dr. Avraham Granovsky (Granott), who managed the Fund's economic activity; a prolific writer, he drafted in numerous books and articles a blueprint for KKL-JNF land policy for the coming decades, he himself serving as Chariman in two of these decades.

The third figure was Joseph Weitz, the "Father of the Forests." During KKL-JNF's third decade he worked alongside Ettinger, learning from him about trees and what was eventually to become an Israeli forest. That period of the great land thrust was later dubbed by Weitz the "conquest of the valleys." To him, the third decade was the most significant and decisive in "expanding labor settlement, developing intensive agriculture and bolstering mixed farming."

The idea of one's own land had become a concrete fact - no longer a ravaged, remote strip of Valley, but moist, brown furrows, intoxicating after the rain. "On the soil of your redeemed fields, grain will make bells sing," wrote poet Nathan Alterman; the words, "…in the Valley, dew will glisten" became a symbol of the renewed spring KKL-JNF brought to the landscapes it had redeemed from other hands.

Alongside its land reclamation and drainage work, KKL-JNF forged ahead with afforestation. Indeed, over the years, afforestation became its hallmark, even more so than land redemption. But of all the forests that the Fund planted before WWI – after the Turks had felled hundreds of thousands of trees for locomotive fuel – only some 14,000 trees remained by the start of the third decade.

This sorry statistic spurred on forest lovers to recover the land with a plumage of trees. In 1920 planning began of the country's future forests, with KKL-JNF eyes – and feet – locating areas unfit for crop cultivation, especially on rocky terrain and slopes, but fertile enough ground for the roots of inedible trees. "The forest heralds the mountain," Weitz said, and the guiding concept that took shape at KKL-JNF at the time was that planting many trees in few places is better than few trees in many places. Unlike the soil, which was redeemed furrow by furrow, forests were not created tree by tree, but by a contiguous mantle of trees that the mountains donned and unfurled over the slopes.

One of the reasons for the increasing momentum of KKL-JNF afforestation during this period was the severe economic situation in the country, and dearth of jobs. Forestry work – mainly preparing tree wells and planting trees – provided many people with a livelihood, just as it was to do again 30 years later, during the great wave of immigration to the newborn State. The Fund's largest afforestation project was at Kiryat Anavim, transforming this settlement dot on the road to Jerusalem into a green spot in the Judean Hills. Many of the pioneers of the Third Aliya made their living planting this forest.

Over a five-year period, forests were planted at nine locations around the country, among them 357,000 trees in the shifting sands near Rishon LeZion. Two of the largest forests of the time were planted in 1928: Balfour Forest, near Kibbutz Ginegar, numbering about 300,000 trees, the first tree being planted by Lord Plummer, the British High Commissioner; and Mishmar HaEmek Forest. Another forest was planted in memory of King Peter of Yugoslavia. Near Kibbutz Sarid, established by immigrants from Czechoslovakia, 13,000 trees were planted in memory of Thomas Masaryk, that country's president. It was the start of the custom of planting groves and forests to honor world leaders who supported Zionism.

In 1926 KKL-JNF purchased 4,000 dunams of land south of both the Sea of Galilee and the farming communities of Kinneret and Deganya that had been established on the Fund's first lands in the region. Four years later, almost at the end of the decade, Yehoshua Hankin succeeded in buying another 3,000 dunams of land in the Beit She'an Valley. Point after point, the Head Office map showed land purchases made and transferred to KKL-JNF, as well as forest areas where planting had begun. A Fund staffer said of those years that whenever he passed the wall with the map, his eyes would light up with pride at the sight of its increasing color.

Photo: KKL-JNF Photo Archive

In December 1926, KKL-JNF celebrated its 25th anniversary and the Fund could take stock of its achievements with satisfaction. As opposed to the early years, when there had been little land purchase, by that landmark 25th year, tens of thousands of dunams were being added each year.

On the Fund lands, owned by the Jewish People, there were now 38 communities; numerous swamps had been drained, and about half a million trees planted. To the 200 thousand dunams of land redeemed during the first 25 years, another 18,000 were added in the 26th year, at Kfar Hasidim, in the Jordan Valley, and around the Sheikh Abreik hills in the western Jezreel Valley. The safekeeping of the Sheikh Abreik area was entrusted to Alexander Zeid, the legendary guardsman of the HaShomer organization. The image of the Hebrew guard (shomer) protecting the lands at the entrance to the Jezreel Valley was immortalized in "Land, My Land," a song by Alexander Penn and Mordechai Ze'ira: "Here, the song of olive crowns, here, my home…"

The Fund's work was also reflected in other poems set to music by Ze'ira in the '20s and '30s. "Hurry, hurry pickaxe, carve out block from rock! Hurry, hurry anvil, rock for road gravel! ("On the Rock," by Avraham Shlonsky); "Plow, plow, my plow, deepen my furrow, now…" ("Sower's Song," by Oded Avisar); and "To homeland vineyards…lead the way, to vale and dale, for nature's holiday, today…" ("Planter's Hymn," by Shmuel Bass).

In those years contributions streamed in to KKL-JNF's coffers from Jewish communities east and west. They hailed not only from the large seats of world Jewry at the time, Poland and the U.S., but also from China and Japan, Morocco and Tunisia, Argentina and Chile, and so on. The Fund's honor roll, its Golden Books, document both the gifts from almost every Jewish community in the world, and the fact that the Jewish world, through its gifts, saw itself as a partner to the Fund's work in Erez Israel.

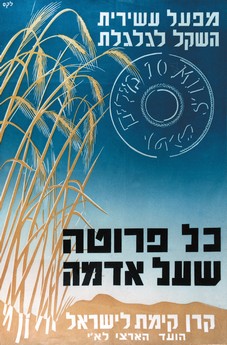

The coins dropped into the Blue Box and the purchase of KKL-JNF stamps were the most meaningful expression of the Jewish People's bond to Erez Israel. The picture of Erez Israel that featured on the stamp journeyed, along with the letter, from one coast to another, reaching the most far-flung places. There, a Jewish child could hold it, "touching" the far-away land and sharing in its redemption.

KKL-JNF emissaries went abroad to publicize the Zionist enterprise wherever Jews lived. Appearing at meetings and conferences, they told of the Fund's work in Erez Israel, of Jewish settlement and the momentum it was gathering.

In 1925 Ussishkin toured the communities of eastern Europe. His journey, characterized by the press as a "propaganda trip," encouraged Zionists to support the Fund's work. A year later found him in western Europe, addressing meetings. Crowds flocked to hear the man who headed a Zionist organization and was said not only to talk, but mainly to do. Some sensed the fragrance of Erez Israel rising from his words. Others said that two of his words – "Erez Israel" – were worth a thousand pictures.

Nathan Bistritzky-Agmon, Director of KKL-JNF's Youth and Propaganda Department, also brought the Fund's message to Jewish communities throughout the world. On one of his trips to Europe, he wrote to his superiors at the Head Office in Jerusalem that he attached great importance to "educating the masses towards Zionist awareness both organizationally and in concrete work on behalf of Keren Kayemeth." His lectures and appearances raised Zionist consciousness, and the "concrete work" of those who chose to remain in the diaspora was to donate more funds to redeem the land. Bistritzky-Agmon knew how "to coax" coins not only from pockets, wallets or bank accounts, but from hearts. To many people, each coin was a furrow of earth, a building block or a water pipe.

Photo: KKL-JNF Photo Archive

Thanks to the vivid information trips, the Blue Box and KKL-JNF stamps, world Jewry saw the Fund not only as an organization that bought and cultivated land in Erez Israel, but one that did more than any other Zionist body for education and information. Its voice, and those of the leaders of the Zionist Movement at the time, literally reached out to all Jews. As part of its information work, the Fund recorded on gramophone the voices of journalist Nahum Sokolov and of "the Father of Settlement," Avraham Harzfeld (in Hebrew); of Zalman Shazar – then Rubashov – (in Yiddish); and of Ze'ev Jabotinsky (in Hebrew, Russian, and Italian).

In one case, in the Jewish town of Aishishok in Lithuania, an "authorized" Fund representative even had a poster printed, inviting the townspeople to a meeting with all the heads of the Zionist Movement. On the appointed evening people gathered in the local synagogue to await the arrival of the distinguished speakers. When the activist appeared, he was asked where all the promised guests were. He pointed to a small case under his arm, and set it down in the middle of the hall. Out came the recorded words. And so it happened that a remote town hosted all the Zionist leaders in a single day: they arrived on gramophone "plates." After "the voice" of Erez Israel was heard, donations were given to make the land bloom. The knowledge that the land towards which they turned in prayer was being built by their own donations brought it all that much closer to them, making it "flesh of their flesh."

The Jewish press that decade documented some highly original KKL-JNF fund-raising initiatives, on the local level. In Vienna, a children's card game was created: all 44 cards, when joined together, formed a picture of a new farming community in Erez Israel. The children learned that the community taking shape before their eyes was being built with Fund monies, monies that came also from the purchase of the game. In many places concerts were held and films screened, with all proceeds going to the Fund. In Galicia, merchants earmarked a per cent of their income on one day of the Hanukkah festival for KKL-JNF. "We must strive," wrote one Fund activist, "to have a Blue Box on the table of every Jewish home for all eight nights of the festival."

In March 1924 the Jerusalem Head Office started publishing a bulletin in five languages. Entitled Our Fund (Karneinu), it was to foster "a sense of fraternity among all those united by their labors for the Jewish National Fund... and strengthen the dual bond that exists on the one hand between the Land and the People and, on the other, among the People themselves."

Mainly however, KKL-JNF's education and information work was directed at the children of Erez Israel. Numerous posters were distributed to schools and youth movements, from which youngsters of both labor settlement and towns learned about the Fund's activities.

During Hanukkah of 1925, writers convened at Kiryat Anavim to try to come up with creative ways to ensure the success of the Fund's future projects and goals – the redemption of another 100,000 dunams of land. According to the local press at the time, the conclave was a historic step aimed at rallying the Jewish People's intellectuals around the National Institution that strove to create a land base for national settlement and mass immigration.

When Berl Katznelson, editor of Davar and Labor Movement leader, was asked as an intellectual about his connection with KKL-JNF, which dealt in the material rather than the spiritual, he answered: "Does Hebrew culture have any greater haven and stronghold today than the land being redeemed by the People and placed at their disposal? Does our generation have any more important cultural assets than the vital concepts of settling people, rooting them in the land, [providing] land for workers? Is there a more enlightened form of education than the values of public service, tilling a dunam, [giving] a penny, and working on behalf of the Jewish People?"

The Kiryat Anavim conference expressed the hope that the call of Erez Israel's intellectuals would arouse Jewish writers in the diaspora - and through them, the entire People - "to mighty deeds for the redemption of the land of Israel." After the authors and poets on behalf of KKL-JNF were organized, it was said that the toil on the soil, which had often seemed drab and difficult, had been transformed into song and poetry. Others said that the Fund had not only purchased lands, but had set down roots for broader segments of Jewish society both in Erez Israel and the diaspora.

In 1926 teacher and educator Solomon Schiller, a KKL-JNF activist, declared that, "children must be involved in the new work taking shape on national land…their souls must be engaged in the redemption of the People through the redemption of the land. In order for schools to don a national form, teachers must not only look favorably upon fund-raising, but organize it as an educational project and charge children with redeeming the land as a national duty."

As a result of these words, in 1927 teachers convened at the Children's Village on the slopes of Givat Hamoreh in the Jezreel Valley to establish the Teachers Council for KKL-JNF. Baruch Ben Yehuda, principal of the Gymnasia Herzlilya high school, was the chairman of the new educational council; a few years later, it changed its name to the Teachers Movement for KKL-JNF.

Addressing the founding conference at the Children's Village, Menahem Ussishkin told the teachers that just as the children were the ones redeeming the Hebrew language, it would be they who would redeem the land as well. The conference recognized the practical aspects of land redemption as the essential foundation for education of the younger generation. Poet Chaim Nahman Bialik said that Hebrew schools were not to rest content with developing a national society, but had to hold up to children national accomplishments, as embodied by KKL-JNF. A call went out to make the Fund's work a part of Hebrew education. The conference acknowledged school involvement in land redemption as a "basic factor in the renewal of Hebrew education and a point of reference for the national and human ideals of the Hebrew renaissance movement." To this end the Teachers' Movement for Keren Kayemeth began to prepare information materials to showcase the Fund's activities.

It was at another conference of the Teachers Movement, two years later at Ben Shemen, that Ussishkin gave what was to become his historic address, "The Voice of the Land." He said: "The penny that a child gives or collects for land redemption is not important in itself, not by it will Keren Kayemeth be built up nor the land of Erez Israel redeemed. The penny is important as an educational element: it is not the child that gives to the Fund, but rather the Fund that gives to the child. It gives him a lifelong foothold and lofty ideal."

Ussishkin exhorted Hebrew teachers to educate pupils in Erez Israel and in the diaspora towards the redemption of the land. Bialik said, "the idea of land redemption must become the symbol of our national rebirth. The words "Keren Kayemeth" and "land redemption" must be so exalted as to allow for multi-faceted interpretation." One result of the conference was that a KKL-JNF corner now graced every classroom, centered on the Blue Box. At the initiative of the Teachers Movement, the schools also revived agricultural festivals: bringing in the Omer - the wheat - and first fruits of spring (Shavuot); the harvest holiday in autumn (Succot) and, of course, Tu Bishvat, "the new year of the trees," which became a tree planting holiday. To help it in its work, the Teachers Movement recruited illustrators, writers, and poets to create songs and stories about the love of the land and the cultivation of the soil.

In cooperation with the Omanuth Publishing House, KKL-JNF issued a series of illustrated books in vowel-pointed Hebrew about the early colonies and their protagonists. Author Moshe Smilansky of Rehovot – who was not only an intellectual but a man of the land par excellence – wrote his Mishpahat HaAdama (The Family of the Land) at the time, as well as other books." Bialik, who also enlisted in the Fund's work, asked at one of his appearances, for a new mitzva to be added to the 613 commandments incumbent on Jews, namely, that of settling and redeeming the land.

In 1926, as KKL-JNF celebrated its 25th anniversary, Bialik coined his well-known saying, that "a nation has no more heaven above it than soil beneath its feet." Bialik told of a professor who had been asked how much land a person needs to feel that he is on a safe footing. It had been explained to him that a man might make do with "a piece of land on which to place his feet"; but, the professor persisted - what about a person standing on a mountain or some other elevation: "How much land would he need for his legs and knees not to quake from fear of falling?" Bialik had replied, "He needs land equal to his full height, so that if he stumbles and falls, he will be on firm ground." And then Bialik told his audience: "I look at the land redeemed by Keren Kayemeth and I ask myself, is the land that has been redeemed commensurate with the stature of the Jewish People? Can it quell the fear of falling? And to this, the answer must be 'no!' For a people of 16 million, of a lofty world stature of thousands of years - the land redeemed thus far is not even enough for his foot. May the day come that the land redeemed matches the full stature of the Jewish People."

KKL-JNF's education and information work not only deepened Zionist education, but provided a livelihood for many immigrants as well, notably for press and film photographers. They were dispatched to agricultural communities established on Fund land to document the farmers at work and the communities that had risen at sites that only a few years back had been dust and dirt. Their films were among the first shot in the country, inaugurating the chapter of Israeli film-making.

First Fruits Ceremony at Shefaya, 1930, a custom revived by the Teachers Movement for KKL-JNF. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

Towards the end of the decade KKL-JNF continued to redeem lands, with stepped-up momentum and under the banner of Ussishkin's motto, "Don't say we'll redeem tomorrow, tomorrow may be too late," which was printed on posters and distributed to schools. Despite the severe economic crisis in the country, which hit the urban population especially hard, and peaked with emigration exceeding immigration, the Fund activities expanded: it purchased two additional valleys – the area of Acre Bay north of Haifa (which KKL-JNF's Names Committee later called Zebulon Valley) and the Hefer Valley in the Sharon, as well as land in the Jordan Valley.

These lands, too, were bought by Yehoshua Hankin for KKL-JNF and with its monies, restoring the Zebulon Valley to the Jewish People 25 years after negotiations for it had been begun by Hankin. The money placed at the Fund's disposal for the purchase of the coastal valley was, from 1924, used not only to redeem additional land, but to save private, urban transactions undertaken by businessmen and companies who could not meet their commitments because of the economic crisis.

KKL-JNF, which was a minor partner in the purchase of the land for Haifa Port and adjacent urban neighborhoods, was quick to conclude the deal with the help of a contribution from the American Women's Zionist organization, Hadassah. Here the Krayot workers neighborhoods were built. Avraham Granovsky supported the urban acquisitions because "the purchase of land in Haifa Bay gives Keren Kayemeth a chance to control Haifa's development by directing land prices, preventing real estate speculation, and impacting on housing conditions."

In his memoirs Ussishkin wrote that on his first visit to Palestine in 1901, he had already regarded the redemption of the valleys - a task he would complete in the third decade - as the great project of the Jewish People. Numerous obstacles, however, had stood in the way of purchasing the Zebulon and Hefer valleys. Only in May of 1929, the year of the Fund's sizable land purchases, did the Hefer Valley become KKL-JNF property.

In order to obtain funding to purchase the Hefer Valley lands, Ussishkin went on a fund-raising mission to Canada in 1927. He told his audiences about the chance to buy up another valley, where once the lands were reclaimed and swamps drained, new villages would be built, housing thousands of families. Canadian Jewry responded warmly with donations for the new project. When Ussishkin returned with the initial funding and pledges to raise additional amounts to purchase the Hefer Valley, he wrote to Yehoshua Hankin: "Well, I've done mine, now it's up to you to bring the matter to fruition." Ussishkin was well aware of the minutiae on which these matters could rise or fall. He made it clear: "This is only the beginning of much greater things to come in other countries, including the U.S.; otherwise, Heaven forbid, all is lost…Keren Kayemeth will vanish from the stage completely and, with it, all land redemption."

In other words, he was telling Hankin that now, with the first funds in hand, it was his job to secure the Hefer Valley, but it was the Fund's good name that hung in the balance. Should the transaction fall through, it would be difficult to obtain funds in the future. Hankin knew the Hefer Valley and the landowners, and was at home in their tents; after years of talks and complex and compound legal problems between owners and heirs, and between them and their mortgagers, and between the latter and their heirs, Hankin was appointed arbiter. He was the seller, in their name, and the purchaser, in the Fund's name. He seemed to be transferring the land from one hand to the other, but primarily to KKL-JNF hands.

At the Zionist Congress which convened in 1929 in Zurich, Ussishkin announced that the Hefer Valley was in "our hands," the gift of Canadian Jewry to the Fund on its 25th anniversary. The Hefer Valley, too, thus evolved from a Zionist dream into a KKL-JNF reality. The Fund planned on settling it during the next decade, as part of its project of the "Settlement of the Thousand."

In January 1930 a group of 30 people - members of the Vitkin and HaEmek organizations – took up residence in the Hefer Valley. They occupied an old house while they drained the swamps and reclaimed the land. The drainage took three years. Only at the start of KKL-JNF's next decade did they set up their village, Kfar Vitkin, named for an educator of the Second Aliya immigration wave.