The tenth decade opened with tree plantings in unusual circumstances. Scud missiles fired from Iraq had landed in Israel the night before. Yet that day, travelers on the country’s roads were asked to stop at KKL-JNF sites to plant a tree. The Information Department changed its planned winter motto of “Arise and Plant” to: “shtilim lamrot tilim – Buds in spite of Scuds.”

Major Tu Bishvat planting ceremonies, however, had to be cancelled because of the Gulf War. Nevertheless, KKL-JNF managed to prepare 20 planting sites along main roads, among them at Latrun, Netanya, Haruvit, Ein HaShofet, Jeru- salem, Ein Carmel, Atlit, Golani Junction, Yatir, and Nahal Duda’im north of Beersheba. The trucks that brought the saplings to the planting sites bore signs warning of: “Sh(t)ilim.” At one ceremony, where cadet pilots joined the planting, an observer quipped: “Flowers were planting trees”; the Hebrew word prahim means both “cadets” and “flowers.”

The plentiful rains that winter facilitated the trees’ acclimation in the soil, and the Afforestation Division, which employed 250 immigrants in forestry work at the time, facilitated the latter’s acclimation in the country.

Despite the difficulties caused by the war, three million trees were planted that winter over 21,000 dunams, more than half of them in the Negev. They joined the other 190 million planted by KKL-JNF since its establishment nine decades earlier. The planters that year included numerous new immigrants for whom this was their first such experience in Israel. At one ceremony, new immigrants from 12 different countries participated and, at many sites, it was for them a first lesson in civics and a first encounter with the homeland soil. Many of them saw it as another stage towards their receiving Israeli “identity cards.” To fix a tree in the ground was to establish a foothold in the homeland.

To assist the national efforts of immigrant absorption, KKL-JNF decided to employ immigrants in a forestry program devised by its Land Development Authority. Not only did it recruit immigrants for work; but it also worked for them by planting cheery trees near their new homes. Two years after the great wave of immigration began, the Fund absorbed into its workforce numerous demobilized soldiers and jobless, including many new immigrants. Once again it found itself helping the state absorb immigration and solve unemployment problems, shouldering a national task.

Alongside the huge job of site preparation for immigrant absorption, the Fund also pushed ahead with afforestation, investing even more in this decade in diversification. A good deal of attention was paid to Galilee forests, with hundreds of thousands of trees planted along the Naphtali Mountain Range from Kiryat Shmona to Manara and Misgav Am.

At the end of 1990, which had begun with Scuds and saplings, KKL-JNF marked its 90th anniversary. “If we look back from the perspective of many years,” World Chairman Moshe Rivlin said, “there is no doubt that our working arena has changed. Yet, I don’t know of many worldwide movements or ideas whose ideological base has remained fundamentally valid after so long a passage of time.” For Rivlin, the Fund’s 90-year history was the foundation of its everyday work all over the State of Israel.

The Knesset marked KKL-JNF’s 90th anniversary with a festive session in which Speaker Dov Shilansky noted that the Fund had remained the key factor in greening and blooming the land.

In the Casino Hall in Basle, Switzerland, where the Fifth Zionist Congress had voted KKL-JNF into being, more than 1,000 Fund activists from all over Europe convened to hear about the past and discuss the future. A special session was devoted to fostering KKL-JNF’s young leadership in European countries.

At Nicanor’s Tomb on Jerusalem’s Mount Scopus, the burial sites of early Zionist leaders Menahem Ussishkin and Yehuda-Leib Pinsker, Fund Board members gathered on the 50th anniversary of Ussishkin’s passing to remember the former Fund Chairman. “As our 90th anniversary begins,” said Rivlin, “we say to these two figures, ‘your work goes forward and your banner is held high. Your spirit and inspiration guide us in our ongoing work’.”

The continuing honor paid the two men 50 years after they were laid to rest was a testament to the triumph of their convictions, and KKL-JNF’s daily contact with the soil 40 years into statehood was a testament to its vitality. The Fund constantly had its hands full – proof, in the face of its detractors, that Zionism’s practical work had not ended with Ussishkin but forged on, day by day, to meet the state’s changing needs.

The tasks had changed over the years, the tools had become more sophisticated, but now, as then, eyes looked in pride to the land. The land was the reason for the Fund’s establishment and the reason it continued to exist. With the year 2000 just over the horizon, KKL-JNF embarked on the 21st century with clear evidence that it still had challenges to meet and tasks to execute. Much work still awaited it in this decade leading up to its centenary and a new century.

KKL-JNF continued to bond the Jewish People to the land of Israel. The numerous reservoirs built during these years thanks to contributions from different Jewish communities reinforced the special bond between diaspora Jewry and the projects rooted in the land. Donors knew that a contribution to KKL-JNF was a contribution to the land, the Jewish People’s most important asset. Without it, the Jewish People had no seat or viability – no water to drink, no air to breathe.

Upon the fall of the Iron Curtain and the collapse of Communist regimes in Eastern Europe, work resumed in many countries that, for years, had been cut off from the Fund and from Israel. In other countries, Jewish communities continued to raise money for the Fund. The Jews of Argentina built a monument to their country’s national hero, San Martin. The Jews of Italy contributed towards the Reshafim Reservoir in the Beit She’an Valley. American Jews continued to plant the large forest near Ness Harim in the Judean Hills, founded on the occasion of the U.S. Bicentennial. The U.S. Jewish community also funded Timna Park in the Arava. The organizations and individuals from the Jewish world inscribed in the Honor Books during this decade even registered an increase, demonstrating that the Fund had kept its warm spot in Jewish and Zionist hearts.

An Ethiopian immigrant at Gilat nursery. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

Every such warm spot mirrored one on the land, imbued by KKL-JNF with new life. The many major projects that rose on the map, merging with or recreating landscapes, made the organization a vivid oasis of Zionist action, largely untouched by the storms that rocked the country. Donors well knew that KKL-JNF retained its place of honor not because of nostalgia for values of old, but because of its abiding work for the future. As a new century dawned, its vibrant energy in this decade, too, remained focused on the colors on the land: green of forest and blue of water, the main threads in the Fund’s tapestry of endeavor.

These years saw both water and fire damage to forests, and foresters, alongside their dynamic planting work, had to heal the wounds of natural and man-made disasters. The first winter of the tenth decade brought a mixed blessing: heavy rain and snow, but also heavy forest damage. Numerous trees broke or fell, particularly in the north, at Biriya and Baram, as well as in the Judean Hills. The major task of the spring of 1992 was to repair the winter damage and to restore tree stands.

The bulk of the work consisted of clearing the forest floor of the large amounts of inflammable debris that had collected before the onset of the long, dry summer months. Another 200 immigrants were hired, bringing the total number of new immigrants at work in Israel’s forests to 600. The Fund again combined assistance to the state with vital conservation work.

In 1993, when Jerusalem marked the 25th anniversary of its reunification, thousands of trees were planted around the heart and capital of the Jewish People. Special budgets were earmarked for the employment of more than 1,000 jobless – new immigrants and demobilized soldiers – in assorted development work. That year, with the help of these employees, another 21,000 dunams were planted, almost half of these in the south: at Nahal Eitan, Kissufim, Nahal Duda’im and Sayeret Shaked Park near Ofakim.

Pines, for years the hallmark of the country’s planted forests, now took a back seat to other species. Many pines, especially at Shaar HaGai on the road to Jerusalem, had been hard hit by the Matsucocus josephi scale insect which, ironically enough, had been named after “the father of the forests,” Joseph Weitz. To rehabilitate the forests, KKL-JNF moved over from monocultural plantings to greater species variegation, including the scale-resistant Brutia pine, other conifers and broad-leaf species. It was the onset of mixed forests.

In addition, KKL-JNF invested in the maintenance of natural woodlands, especially in Galilee, and in reviving the country’s rivers. In the early 1990s KKL-JNF and the Ministry of the Environment had established the River Rehabilitation Administration to clear the country’s waterways of pollutants and restore riparian landscapes. KKL-JNF field workers exchanged their footwear for gumboots as they waded into riverbeds to carry out extensive clean up and drainage.

The year 1993 was “Reservoirs Year” as long-term effort and planning paid off in the increasing emergence of blue in KKL-JNF’s spectrum. Storage facilities were built near Kibbutz Gesher and Kibbutz Maoz Haim, joining others already completed in the Beit She’an Valley, as well as in Lower Galilee and around Jerusalem. The most important endeavor of this decade was thus one carried over from the previous one – water conservation.

At the start of the decade, KKL-JNF Director General Ori Orr had said, “Keren Kayemeth will lend a hand to solve one of the most critical problems facing the country: increasing the water resources available to agriculture, the country and its residents via modern means adapted to each region and every problem.” The motto was to resound throughout the decade, with the Fund going to great lengths to conserve water, enrich the water table, halt erosion and flooding, and reclaim the soil.

Reshafim Reservoir - one of 115 built by KKL-JNF in the 1990s. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

KKL-JNF publicity campaigns asked supporters around the world to “give Israel a drop of life – water.” Water harvesting in storage facilities provided many areas with resources for farming and also became an element incorporated into parks for leisure and recreation. By creating such new income sources and economic activity, the Fund strengthened the residents’ hold on the land and deterred them from abandoning it.

KKL-JNF continued tilling both land and “spirit” as its new Director General, Izhak Elyashive, took up office, and in his eyes – after 16 years as head of the Azor Regional Council and then as Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Postal Authority – “the Fund was the only national organization to combine land reclamation, road-blazing and education.” Born in Poland, Elyashive had spent three years at a Displaced Persons camp in Germany, learning at a young age the importance of the Fund’s land reclamation for the benefit of every immigration wave, one of which had brought also him to the country.

In a single year KKL-JNF built a record 23 reservoirs throughout Israel, 10 of these in the Beit She’an Valley where another half-dozen were to spring up. During the tenth decade, it finished building a total of 115 dams and reservoirs with an overall capacity of 100 million cubic meters of water. This amount, about 5% of the annual average water consumption, was an important savings of a vital commodity that would otherwise have been lost to the sea.

In 1993 KKL-JNF returned to reclaim the Hula Valley once more. It came full circle as it were, just as it had done in returning to the Jezreel Valley 50 years after draining its swamps. The Hula, which had been made fruitful by what in the 1950s had been one of KKL-JNF’s greatest achievements, was “ailing.” And so, four decades after its draining which had added 60,000 dunams to the agricultural cycle, 1,000 dunams were now reflooded. In the spring of 1994 the Jordan River was rediverted to its original course, and water began to flow into a new small lake. The result was a boon to the region, with this part of the Hula Valley again serving as a habitat for aquatic birds and plants as new roads brought tourists in their wake.

The main reason behind the Hula’s redevelopment, however, was to prevent pollutants from flowing into the Sea of Galilee, Israel’s main surface reservoir, which feeds the National Water Carrier. Deteriorating and sinking peatlands had begun to damage crops and farmers had been abandoning the soil, fires were spontaneously ignited and rodents and other pests were rife. Nitrates from the neglected, non-irrigated lands were being washed into the Sea of Galilee. Planners sought a solution that would not only protect the country’s main water source, but also serve agricultural and tourism needs so that the land and landscapes would enhance the livelihood of residents and keep them on the soil.

The clouds of black dust rising above the Hula were a sure sign that 80 Fund bulldozers were at work in the valley below, in a huge environmental project in which some $25 million was invested. By a quirk of timing, the completion of the second stage of the Hula’s redevelopment in the 1990s coincided with the completion of the same stage of its work back in the 1950s.

The new project included the construction of a dam over the Jordan near Kibbutz Kfar Blum. This dam, along with a water diversion mechanism, was described by Hula project manager Giora Shaham as the axis of the entire project. When it was completed two years later, the restored, historic wetland became a small lake with a boating canal, surrounded by trails, bridges, and broad infrastructure for diverse tourism.

Roadbuilding also proceeded in this decade and, in conjunction with the Public Works Department, KKL-JNF also began to plant trees and shrubs along new highways and old roads in the center of the country. The landscaping not only added an element of green for driver pleasure, but helped conserve soil in the face of roadworks. Following the successful landscaping of the Gannot Interchange, the project was extended further afield.

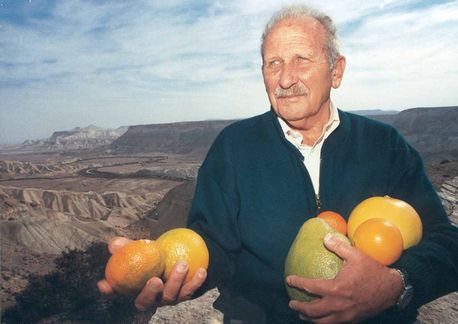

Citrus fruit in the Negev, held by LDA head David Nahmias. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

The new trees along numerous roads were suited to local vegetation that had been damaged by asphalt and soon looked as if they had always been there. In some cases, trees had to be transplanted. Thus, dozens of old Galilee olives wee moved to Shaar HaGai Junction, acclimating so well that they seemed to be “native.”

At mid-decade KKL-JNF again had to defend its “handiwork.” The extreme heat wave of the summer of 1995 dealt one of the gravest blows ever to the country’s forests, notably along the road to Jerusalem. The fire, which broke out at 11 a.m. on July 2 near a poultry run at Moshav Mesilat Zion, was swiftly fanned by hot dry winds. Westerly gusts caused it to leap across, first the Shaar HaGai-Beit Shemesh highway, and then the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv highway. “It was like a hurricane of fire,” the Givat Ye’arim fire-spotter said. Their eyes tearing and burning, old-timers at communities on the road to Jerusalem watched the flames consume trees that 40 years earlier they had planted with their own hands in tree wells dug out by their own feet.

Only after the flames were totally extinguished could the heavy toll be assessed: about 1.5 million trees lay charred over some 12,000 dunams. The acrid odor hung in the air for days. The black hills were a bleeding scar.

The grief was great, but KKL-JNF had gained much experience of fire and arson over the past decade and it quickly set to rehabilitating the area and lending it a Mediterranean aspect. A steering committee, made up of professionals from many different quarters, decided on the image of the regenerating forest winding its way up to Jerusalem. KKL-JNF again showed that whenever a forest was destroyed by fire, it soon stepped into the breach to restore the green that had been scorched by flame.

Forest fires broke out in the summer of 1996 as well. That summer KKL-JNF also lent a helping hand to northern communities in the aftermath of the Grapes of Wrath military operation in Lebanon. As an immediate measure, it made its fire-extinguishing equipment available to battle flames sparked by the launching of Katyusha rockets from Lebanon. Later, it worked on enduring projects for “future generations,” building roads, preparing additional land for crops and orchards, and solving water problems through drainage jobs. Thirty-four kilometers of roads were built in Upper Galilee, 23 in Galilee, and 76 in western Galilee within the jurisdiction of the Mateh Asher Regional Council. Along with the roadworks of previous decades, KKL-JNF bulldozers had carved out a total of 7,000 kilometers of roads, crisscrossing the country like capillaries, veins and arteries which, if lined up end to end, would span its width and breadth several times over.

Also in 1996, Jerusalem celebrated its 3000th anniversary. To mark the event, KKL-JNF gave the city Gan Yaldei Yisrael in the Jerusalem Peace Forest, a gift from Jewish children everywhere on this special occasion. The Fund also established an expansive park in the Eshtaol and Shaar HaGai Forests in memory of assassinated Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. It encompasses Burma Road, the Jeep Trail and the Harel Lookout, areas in which the Harel Brigade under Rabin’s command had fought during the War of Independence. The historic milestones became heritage sites focusing on Rabin’s military career, while trees in bud reflected the longing for peace in whose service he gave his life.

At summer’s end in 1998, towards the close of the Sukkoth holiday, another scourge of fires swept over the forests. It wrought havoc on planted forests, natural woodlands, orchards and homes at the communities of Ein Hod and Nir Etzion on the southern Carmel, and in Haifa’s Denya neighborhood. And KKL-JNF once again showed that in this battle against destruction and natural forces, the human touch and “green thumb” ultimately prevailed, even if the task at times seemed Sisyphean, restoring to nature what had been taken from it. KKL-JNF, once again, was artist and craftsman, its caress soon repairing disfigured landscapes.

In the wake of the fires, which by a single gust consumed thousands of planted and natural trees, KKL-JNF turned to foresters in other countries in order to learn additional ways to fight fire and rehabilitate burnt forests. This fruitful cooperation led to the Fund’s becoming teacher as well as student.

Lachish Park. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

Basically, the forestry word that went forth from Zion said that afforestation on the edge of, and in, the desert itself halted desertification or the encroachment of arid lands. In 1994 the Fund hosted an international conference on arid-zone management, presenting Israeli planting advances in areas of minimal precipitation.

In 1995, to significantly boost agriculture and settlement in the arid south, the major project of Action Plan: Negev got under way to accord the region top national priority. The guiding spirit behind it was David Nahmias, Director of KKL-JNF’s Land Development Authority. Other partners were the Ministry of Agriculture and the Jewish Agency. Some U.S. $250 million was invested over a three-year period to develop water sources, hothouses, and even citrus groves – never tried before in the desert – as well as fishponds and olive groves. The project was launched by the late Prime Minister, Yitzhak Rabin, in the Besor riverbed between two KKL-JNF reservoirs.

The rural area embraced by the project included some 100 communities. KKL-JNF had resolved to combat the dry Negev’s failing image and prove that this region of beleaguered agriculture and high unemployment could be transformed into a breadbasket. Action Plan: Negev sought to promote the southern sector of sun-drenched settlement by utilizing its relative advantages. The key was water: clearly, any development in the south depended on augmenting available sources. This meant constructing dams and reservoirs to harvest winter floodwaters that would otherwise go to waste.

The program gave the Negev a new look – rows upon rows of fragrant citrus trees, till then the hallmark of the Sharon Plain. As the scope and viability of citrus raising declined in the center of the country, the branch expanded at an unexpected location – the Besor region, where soil and climate had been found to be suitable. Negev old-timers could not believe their eyes; never had the citrus fruit and spring scents reached so far south. Visitors thought they were seeing a mirage, they had to touch this wonder growing in the middle of nowhere.

Action Plan: Negev also brought the olive revolution to the south, those silver-leafed trees native to the landscapes of Judea and Galilee. Five thousand dunams were planted near Kibbutz Revivim, and the infrastructure for an industrial oil plant built nearby. As an experiment, 50 olive trees from Galilee were transplanted at Kibbutz Neot Semadar in the Negev. Once the trucks and cranes left the site, they looked as f they had been growing there for decades. The very first yield turned into olive oil.

Equally unbelievable were the fish that Action Plan: Negev brought to the desert! Again, in response to growing demand in Israel and abroad, fish ponds began to “bloom” in the central and southern Arava, in the Sedom Plain and the Negev highlands, breaking the monotony of the ochre landscape with splashes of blue.

To finance all these large projects, sizable contributions were needed and they continued to fill KKL-JNF coffers. KKL-JNF Britain hit on an original fundraising means for a new reservoir – a 5,000-kilometer rally of 23 vintage cars from London to Jerusalem, including a 1924 Lancaster, a 1930 Bentley and a 1996 Jaguar. After setting out from Parliament in London and traversing all of Europe to Greece, the convoy of cars ferried across the Mediterranean to Haifa Port. Welcoming them at the Knesset grounds, Knesset Speaker Dan Tichon noted that the rally was living proof that KKL-JNF marched with the times if, instead of Blue Boxes, it was now using cars to raise money. The rally became a biennial event.

Not only cars were used to cement ties with the diaspora. In 1996 KKL-JNF joined the information era when it launched its website. KKL-JNF foresters later convert virtual trees into real ones.

At the end of the decade the forests again came under fire. The unrest that erupted in September-October 2000 and became known as the al-Aksa intifada did not spare the trees. KKL-JNF foresters battled some 300 fires, mostly in the north of the country. The main damage was in western Galilee, around Yehiam and Klil, where flames lapped up some 3,000 dunams of planted and natural woodlands. Tough, hard field workers unabashedly shed a tear at the sight of hundreds of green dunams suddenly turning to black ash. But the work that had gone on for a century continued now, too, and after the fire and wind and water, KKL-JNF returned to what it saw as the vital foundation; to the land.

Widening the Yarkon riverbed, 1992. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

As the Fund approached its centenary, its forests boasted a wide variety of trees; 45% were still pine, but alongside these, there were now eucalyptus, planted not only for scenic diversity but to create new “grazing” areas for bees whose nectar sources had been seriously curtailed by accelerated urbanization. There were also broad-leafed species and fruit-bearing trees, including olives, carobs, and date palms.

KKL-JNF nurseries at Golani Junction in the north, Eshtaol in the Jerusalem Hills, and Gilat in the Negev produced more than three million saplings a year. “What’s special about our forests,” said Zvi Avni, Director of the Afforestation Division, “is the attempt to break into virgin areas, especially on the edge of the desert.” Thirty years after the successful planting of Yatir Forest, the Afforestation Division could look with pride at the trees that had been planted in the Negev and grown into windbreaks.

If in the Fund’s early years tree planting was a means of holding onto the land, creating national ownership facts on the ground and providing shade, now, at the end of its first century, forests were multi-purpose. Israel’s forests at the start of the 21st century served recreation and grazing needs, prevented erosion, rolled back the desert, created “green lungs” and curbed the dust; they were a “softening agent,” as foresters put it.

The opening of the forests to the public, a trend that had begun in the 1970s, gained added emphasis as the centenary drew nearer. Free of charge, KKL-JNF’s forests, parks and recreation areas attracted an annual average of 12 million visits! Moreover, the Fund began to make its forests more accessible to the physically challenged (including “green” WCs for bio-degradable waste).

KKL-JNF also brought environmental art to the forests during this period. Teacher training students conducted a project at Neveh Ilan Forest near Jerusalem, producing a new KKL-JNF outdoor logo: the statue of a bird with blue wings and a green wooden body, representing the plantings and water that the Fund restored to the soil, was installed at 50 parks and forests all over the country, including at Eshtaol, Shaar HaGai, American Indepen- dence Park, and Defenders Forest.

On the cliff overlooking the Ramon Crater, the Fund constructed the Albert Promenade, graced by environmental sculpture. Twelve stone sculptures were also installed along the Electricity Route through Ben Shemen Forest, converting an eyesore into an open air museum, the raw material being the debris of development work carried out by the Electric Corporation. At President’s Forest, planted in the early 1950s and named for Israel’s first president, Chaim Weizmann, a Sculpture Route was installed to blend in with the forest landscape.

At the end of the decade, hundreds of pieces of KKL-JNF’s heavy machinery were busy in land reclamation and, day in, day out, Fund workers were to be seen all over the place – planting and pruning forests, executing earthworks and preparing infrastructure, constructing reservoirs and reviving the country’s rivers.

The Alexander River in the Sharon Plain had been dredged, the 80,000 cubic meters of earth removed slated for elevating the surrounding terrain.

The Afforestation Division was busy trying out a new method to improve water availability to recently-planted saplings. Having long invested great effort in preserving forest inventory, it was also paying attention to the ecological aspects of flora and fauna. Birds, for example, were valued not only for their symphonic offering but as natural assistants in forest conservation and development.

Poleg riverbed after rehabilitation. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

During this period, KKL-JNF also undertook to restore Yeruham Lake and transform the environs into an urban park. In the Negev town of Sderot, the Fund was turning open spaces into public parks. In Kiryat Malachi, the Jubilee Promenade was dedicated and, in Ofakim, another urban park. At the latter southern town, KKL-JNF was also helping recycle sewage water into water reservies for the development of large parks. In Mitzpe Ramon, it was busy carrying out earthworks for a new landing strip to bring the peripheral town closer to the center of the country and promote development, tou- rism and employment projects.

Other activities at this time included installing a monument at Polish Jewry Forest in memory of educator Janusz Korczak, who had accompanied his charges to death in the Holocaust. At the Kibbutz Lavi Planting Center near Golani Junction, a pilgrims grove was inaugurated.

With the end of KKL-JNF’s first century clearly in sight, World Chairman Moshe Rivlin could be heard to say that, “the Fund is still preparing the land to make it possible to settle more and more Jews and connect them to the land, its vistas and scenery. Keren Kayemeth is still creating a homeland.” On another occasion he said, “the land on the edge of the desert has become fertile and populated and Keren Kayemeth has played a mighty role in these achievements. There is still much to do, and Keren Kayemeth will do its part and more. It will always stand beside the State of Israel to preserve it as a fertile, populated land, a land of fruit and harvest, of forest and woodland, of landscapes and nature’s secrets, a land of beast and fowl, of flowing water, recreation and well-being.”

The same goals were on everybody’s lips in 1998 at the changing of the guard when Shlomo Gravetz was elected Chairman of the Board of Directors and Yehiel Leket, Co-Chairman. To help achieve them, Gravetz advocated more public exposure for KKL-JNF to enhance its good name and garner support for its goals.

A native of Moshav Nahalat Jabotinsky near Binyamina, Gravetz saw himself as a link in the chain begun with his parents’ arrival in the country. They had come as pioneers to build up the land, work that embodied the Zionist dream and that he, as Fund Chairman, was continuing. To his mind, the task was one and the same, and would remain so in the new century: to ensure that the Jewish People remain true to the land of Israel, and retain the cardinal principle of national ownership of it.

Yehiel Leket, who had served on KKL-JNF’s Board of Directors for 12 years before assuming office, advocated adapting the Fund’s modus operandi and organizational structure to changing circumstances. He wanted to stress education and attract more pupils and teachers to educational activity in the spirit of the Fund’s vision and experience. “We will become more involved in ecological education because this is becoming a key issue on the public agenda and anyone seriously involved in this work has a germane role to play… The state is both the state of all its citizens – and of the Jewish People. There is no contradiction here. As part of the majority, I have a right to define the state as I see it, historically. Because of the pubic debate surrounding the subject, Keren Kayemeth – which has always dealt in education – was, and will remain, highly relevant.”

KKL-JNF, whose chief concern has always been the land, vows to protect it. On its centenary, its leaders vow that the Fund will not neglect its water-related work, which is so vital to land development, or settlement, or education or diaspora relations. Major land projects of national importance will continue to hold its attention, including the question of national land ownership in the spirit of the vision of its founding fathers 100 years ago.

Side by side with guarding the brown and the green, numerous projects will revolve around blue, not only of river rehabilitation but of water in general. The constant refrain for the coming years will certainly be: water, water, and more water.

The Fund’s goals for the 2000s, as defined by its restructuring, reaffirmed – albeit in different words and according to the state’s changing needs and challenges – the resolutions of the London Conference of 1920 and of its Covenant with the State of Israel of 1961. No matter how often the Fund’s goals and aims were re-examined, one word never changed: “land.” And one phrase, like a mantra, ever guided it: “for and on behalf of the Jewish People.”

A hundred years of non-stop work in which KKL-JNF met the challenge of national land have shown, as one of its leaders once expressed it, that the Fund (Keren) is abiding (Kayemeth). It needs another thousand years at least to complete its mission of green and fill the entire picture – against the Mediterranean background – in hues of brown, green and blue.