Almost ten years after its establishment, KKL-JNF could take pride both in the lands it had purchased and the fact that quite a few of them were already settled. They included a city (Tel Aviv), a collective community or kvutza, (Kibbutz Deganya), a training farm (Moshav Kinneret), and educational projects (high schools in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and Haifa). Lands had been purchased for higher education as well: Jerusalem's Bezalel School of Art and Design, as well as the lands on which the Technion would be built in KKL-JNF's second decade, and the Hebrew University, in its third. Also during this period, KKL-JNF had planted its first forest, Herzl Forest at Hulda.

During its early years of activity, KKL-JNF's representatives in Erez Israel strove to establish a foothold in the Jezreel Valley by purchasing a piece of land there. Until that time "the Valley," as it was known, had been a distant Zionist dream. Its wide expanses of marshland were seen through Zionist eyes as land that could fulfill all the hopes for Hebrew agriculture and accommodate all the forms of Hebrew settlement. In 1910 Yehoshua Hankin, the well-known land redeemer who purchased lands for Baron de Rothschild's Jewish Colonization Association (ICA), bought up 3,500 dunams in the heart of the Jezreel Valley. This man – without whom, according to historian Alexander Bein, land purchase on behalf of the Jewish People would be scarcely imaginable – was well versed in the rules of the game. Calling on circuitous maneuvers in some instances, and sharp negotiations in others, he perfected the art of land purchase and title transfer.

"Land purchase", wrote historian Yitzhak Ziv-Av, who was for many years was a member of KKL-JNF's Board of Directors, meant "unravelling a tangle of registrations, hazy borders, ownership rights and inheritance quarrels; greasing the palms of Turkish pashas with silver; and patience, patience, patience." Again and again, mounted on horseback, Hankin rode out to tents in the heart of the desert, to clay huts in the Valley, and to the mansions of rich effendis for protracted, laborious negotiations until, finally, he returned to Jaffa to announce that he had purchased the Valley from the Sursuks, a Syrian family living in Beirut, whose lands were worked by tenant farmers.

The Valley, at the start of the second decade, was a dream come true. Only when Hankin returned to Jaffa, his eyes alight with excitement, did he reveal that he had obtained the down payment that he had paid to Sursuk as a loan from one of Sursuk's own relatives, which had entailed travelling overland to Egypt. All the tracts that Hankin acquired were the result of persuasive trips and long journeys by horseback to landowners, their representatives, their heirs, and anyone else who might possibly help untangle the knot of multiple ownership and rivalries. He spent many hours drinking coffee by campfires at night and smoking water-pipes in tents by day, in order to restore more and more land to the bosom of Zionism.

In 1911 the first Jewish community arose in the Valley, on the first lands redeemed there, the lands of Fuleh. Settled by veteran members of the HaShomer labor guards organization, the community formed the cooperative farm of Merhavia. Thus, the farming community transformed the Valley from a quaint, far-fetched dream into the buds of a blossoming reality. It was based on the ideas of Jewish sociologist Franz Oppenheimer, an international expert on settlement, who joined the Zionist Movement and was soon nicknamed "the doctor of society." At the height of WWI, another HaShomer group settled another tract of land purchased by KKL-JNF; this second community in the Valley, Tel Adesh, later became known as Tel Adashim.

In 1912, KKL-JNF founded another farm, an experimental farm at Ben Shemen, where the first attempts at mixed agriculture were conducted. Agronomist and botanist Yizhak Wilkansky was appointed director, and he not only greened the hills on the road to Jerusalem, but also had them bear fruit and vegetables. Travellers from Jaffa to Jerusalem at the time could see Zionism renewing its acquaintance with the soil, making an effort to understand it, learn what was good for it, and triumph over two thousand years of neglect. Here one could breathe in the first scents of an Israeli village.

The Fund was now into its second decade of dealing with the soil, redeeming "a dunam here, a dunam there" through agents familiar with the pathways of the desert, the lifestyles of the landowners, and the legal intricacies involved in every deed transfer. On this soil, the Fund continued to lay the foundations of the Zionist enterprise – and the solid foundations of the Zionist spirit.

During this period, the Ezra Association in Germany announced its intention to establish an institution for technological studies in Haifa. For this purpose, KKL-JNF purchased land in Haifa's Hadar HaCarmel neighborhood, on the slope of Mt. Carmel, and in 1912, laid the cornerstone for the Technion's first building. The Eleventh Zionist Congress, convening in Vienna in 1913, recalled another idea that had been raised by Prof. Zvi Hermann Schapira at the First Zionist Congress: to establish a university in Erez Israel, and KKL-JNF was asked to purchase land for this, the first academic institution in the country. Arthur Ruppin, Director of the Palestine Office, conducted lengthy negotiations with Lord Grey Hill, an elderly Englishman who lived in a house he had built on Mt. Scopus in Jerusalem. With the help of a donation from the well-known philanthropist, Yitzhak Leib Goldberg, the transaction was concluded and the lands of Mt. Scopus were transferred to the Fund. Here, in the middle of the next decade, in 1925, the Hebrew University was inaugurated.

Another of Ruppin's many activities was the establishment of residential neighborhoods for immigrants from Yemen, brought to Israel by the first shaliah (or emissary), Shmuel Yavne'eli. The latter's journey to Yemen in 1910 was financed by KKL-JNF and the Palestine Office, and when the immigrants arrived in Palestine, KKL-JNF was also a partner in their absorption, building homes and auxiliary farms for them at Mahaneh Yehuda in Petah Tikva, Shaarayim in Rehovot, Nahliel in Hadera, as well as in Rishon LeZion, Nes Ziona, Zichron Yaacov, and Yavne'el.

To observe first-hand the needs of the immigrants, the Chairman of KKL-JNF, Max Bodenheimer, along with a member of the Board of Directors, paid a visit to Palestine. They decided that what the immigrants needed was not "first aid," but to be settled in veteran colonies and towns, with their own small farms, from which to live off. This model was to be repeated by KKL-JNF at other occasions in its century-long history for it regarded immigrant absorption as a valuable educational vehicle to bond immigrants to the land. It was also an additional vehicle to rescue the soil from wilderness and neglect.

According to the minutes of KKL-JNF's Board of Directors and the Zionist Congresses of those years, the fact that the Fund veered from its primary purpose of land purchase to invest also in other endeavors, especially education and immigrant absorption, fed numerous debates and discussions. It was left to Bodenheimer to explain, in both speech and writing, that these "other" activities were not a "digression" from the "straight and narrow", but rather a reinforcement of the primary goal of redeeming the land. There was no point in buying lands if laborers were not trained to settle them and the lands remained desolate. Building homes for workers, financing an expedition to bring immigrants to the country, helping to settle immigrants and investing in the country's cultural life all contributed to this same goal, he believed.

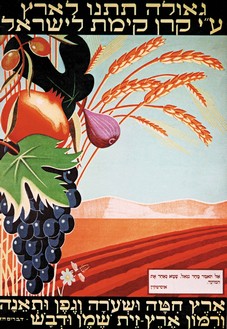

Photo: KKL-JNF Photo Archive

It so happened that whenever Bodenheimer found himself defending those of KKL-JNF's activities that were not strictly land purchase for agricultural settlement, his audience – a mix of supporters and opponents – all applauded him. Years later, there were those who said that by its educational and immigrant absorption work, the Fund had deepened its roots in the land and increased the measure of redemption it brought to the soil; for real redemption is settling, developing and reclaiming the land, restoring to it its colors and scents. Redemption is not reflected merely by land deeds or registration, which are open to and understood by few, but by what the eyes can see: a tree or neighborhood, a village or town, a school or university. As one of the Board members said at that time, land redemption can be smelled, it can be touched by hand or foot on a plowed furrow or a Zionist enterprise sprouting on the land and striking deep roots within it.

In 1913 KKL-JNF purchased the land of Dilb, west of Motza en route to Jerusalem, and during WWI settled a workers group there. This, at the end of the war, became Kibbutz Kiryat Anavim.

By the eve of WWI, KKL-JNF's land assets had reached 16,380 dunams. The largest tract of land owned by the Fund was at Merhavia, a sizeable acquisition that put down Jewish stakes in the heart of the Jezreel Valley. KKL-JNF held only four per cent of all Jewish-owned land in Palestine, but it was on its tracts that the great "revolutions" took place, much more so than on the 58% of Jewish-owned land held by Baron de Rothschild. On Fund land miracles took place, because the communities and fields there changed the face of the territory beyond all recognition, issuing novel modes of settlement.

The guns of August 1914, which opened the four-year long First World War, almost paralyzed KKL-JNF's land redemption activities. One hour before the border between Germany and Holland was closed, Max Bodenheimer succeeded in getting important Head Office documents onto two train cars bound for the west. Bodenheimer, who was a German citizen, resigned from his position as Chairman so as not to implicate the Fund as having German connections.

With the move of the Fund to its third home in the Hague and an end to the Cologne period, KKL-JNF could be congratulated on its efforts to create new forms of agricultural work in Erez Israel, aimed at providing the Jewish People with a land, and training them to till it and live off it.

The start of the Hague period was overshadowed by war, with many eastern European communities suffering economic hardship and halting their contributions. The severance of communication with Russian Jewry and subsequent Communist revolution spurred the Fund leadership – under Dutch banker Jacobus Kann, who managed most of its wartime affairs – to direct their energies towards the United States, which was rapidly becoming the largest seat of world Jewry. Consequently, despite the war and disconnection from veteran donors, KKL-JNF's income actually increased during the period. The monies were used mainly to help the Jewish community in Palestine get through the war, hunger, deportations, and also a locust plague. From the new offices in the Hague, funds began to flow to Jews on the brink of starvation, and to veteran colonies for the defense and protection of Jewish settlements and lands.

To ease the suffering of the urban population in Palestine, all the settlements on KKL-JNF land in Galilee and the Jezreel Valley dispatched large quantities of wheat to Jerusalem. These sacks, in the first year of war, supplied Jerusalem with its much-needed bread. In addition, to provide work for the farming communities, KKL-JNF for the first (but not last) time initiated relief works, mainly draining swamps, improving soil, planting trees and paving roads, activity that not only furnished a living, but also protected the lands purchased and improved the agricultural infrastructure at Kinneret, Merhavia, Deganya, and Ben Shemen.

Even in the difficult years, KKL-JNF never lost touch with the land. When circumstances did not allow for additional purchase and redemption, the Fund concentrated on protecting its holdings, ensuring that the war years did not undo its achievements.

About six months after the British conquered Jerusalem, with the canons still sounding in the distance, Professor Chaim Weizmann laid the cornerstone for the Hebrew University of Jerusalem on Mt. Scopus. Thus, KKL-JNF's first post-war act connected to another idea conceived by its visionary father, Zvi Hermann Schapira; and the Fund could take pride in the role it had played for both the first Hebrew technological institute (that had already risen) and the first Hebrew academic institution (that was to rise in the coming years).

Upon the start of the new era in Erez Israel, which was now entirely in British hands, and in the wake of the Balfour Declaration, which recognized the Zionist Movement and held out the promise of a Jewish national home in Palestine, KKL-JNF published a manifesto reporting on its wartime activities and its plans for the future. The document, distributed throughout the Jewish world in September 1918, called for the strengthening of the Jewish community in Erez Israel as the kernel of the future Jewish state. "There is no assurance of a Jewish community in Palestine" – it said – "unless the Jewish People return to strike deep roots in the homeland soil and bring forth fruit by the toil of their hands… the rooting in the land of poor or penniless Jewish masses is a necessary condition for the creation of a farming class that will do its own work."

In September 1919, banker and economist Nehemia de Lieme, who stemmed from a religiously observant Dutch family, was chosen to head KKL-JNF. The Head Office moved again, this time to London, its fourth home since its establishment. De Lieme had been part of the committee that had managed the Fund's affairs during the war and, after it was over, he demanded that the Zionist Institutions make agricultural settlement their top priority. "Even if we become masters of the land," he wrote in an article outlining the Fund's principles, "ultimately, it will belong to those who till its soil."

The next year saw the close of almost two decades of KKL-JNF work, in which the Fund had become not only a land-purchasing body, but also the Zionist Organization's settlement agency. In order that it might continue to pursue its primary function – without which there would be no need for the second – the 1920 London Conference of Zionist representatives set down KKL-JNF policy for the coming years: "The fundamental principle of Zionist land policy is that all land on which Jewish settlement takes place should eventually become the common property of the Jewish People," the London Resolution pronounced at the end of the Conference. Furthermore: "The instrument of Jewish land policy in town and country is Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael [Jewish National Fund]." The Fund's main objects were clearly redefined: "To use the voluntary contributions received from the Jewish People in making the land of Palestine the common property of the Jewish People; to lease the land exclusively on hereditary leasehold and on hereditary building right..."

Among other things, the London Conference also decided to establish Keren HaYesod (the Foundation Fund) to manage the Zionist Movement's capital and economic activity. Nevertheless, KKL-JNF was not only to continue its land-purchase work, but "to assist the settlement of Jewish workers without sufficient means; to safeguard Jewish labor; to see that the ground is cultivated, and to combat speculation." Armed with this "seal of approval," KKL-JNF threw itself into the task of preparing more and more land for the Jewish People… furrow by furrow.

The Jezreel valley, a short period before KKL-JNF redeemed its lands. Photo: KKL-JNF Photo Arhcive

KKL-JNF's conviction that the land it acquired had to be the national possession of the entire Jewish People was shared by leaders of the Labor Movement in Erez Israel. Berl Katznelson, one of the heads of Labor Zionism at the time and active in KKL-JNF noted: "Zionism, like other national movements originating in human liberty and the desire to elevate man, is characterized by its human, social, and cultural values. Keren Kayemeth, which is Zionism's ambassador, by its actions attests to the nature of these values. Anyone, who delves into Zionist philosophy, realizes that KKL-JNF is no random phenomenon. Not by chance did Herzl and Schapira dream of a Keren Kayemeth [enduring fund] rather than of a land purchasing company. Nor by chance did the redemptive principle of Hebrew labor – rather than the toil and backs of others – become the principle of KKL-JNF."

Freed of its secondary function, that of finding settlers for its lands, KKL-JNF could now concentrate on redeeming the land: not merely by purchasing it, but by preparing it for settlement; not merely in lawyers offices and with legal documents, but out in the field itself on barren hills and abandoned rocks – by clearing stones, draining excess moisture, embarking on first plantings.

The Fund's work may be seen as two hands: in the one, a pen; in the other, a spade. One hand surveyed the terrain, the other tilled it. One hand extended from a sleek business suit, the other, from dusty overalls. Both roles were widely perceived in Menahem Ussishkin, who was to head KKL-JNF in its third decade and literally, wore two hats: at the Zionist Congresses he sported a top hat; but when visiting Galilee or the Negev, he donned a farmer's cap.

Upon the redefinition of the Fund's functions, KKL-JNF's Hague offices began to speak of "reclamation" and "restoration," two tasks that were now within its official purview. They now meant also supplying water to new communities, for without water – the soul of the soil – the Zionist enterprise could not develop. In post-World War II photographs of the Jezreel Valley, KKL-JNF staffers and Valley residents can be seen draining swamps and laying pipelines.

As the second decade drew to a close, KKL-JNF had its sights set on several large tracts of land, especially in the valleys; these, too, were still remote dreams, but no effort was to be spared in bringing them within reach. Gazing down onto the valleys through their binoculars, staffers could see only festering swamps. But, the Fund's work, they knew, would transform the desolation and stagnant water into broad expanses dotted with the gleam of wheat, the green of trees, and the strips of fields plowed and sowed. The weary, malaria-infested land promised no rose garden, but the hard soil posed no real hardship. The land was the goal.