The new decade in KKL-JNF history began by marking 100 million planted trees in Fund forests. It was an impressive figure, yet the Fund would not rest on its laurels and afforestation continued apace. Each year, 600 thousand trees were planted, after careful selection of suitable species and increasing diversification. Each year, new trees cloaked more rocky hillsides in a mantle of green.

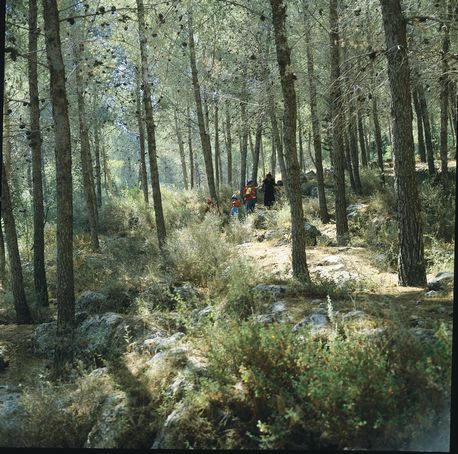

Alongside the veteran pines, new plantings now included the cypress and Judas tree, causing even people familiar with the world's great, variegated forests to marvel at how well they took root in Israel and the palette of greens they added to the pastels of Erez Israel. A visiting American journalist at the time remarked on the "colorful kaleidoscope of hues of green," and many spoke of the "renaissance" of Israel's forests at the sight of new trees conquering barren slopes. The fact of Israeli forests was now visible from afar by means of photographs distributed all over the world. More and more forests were added to the map, bringing wood scent, cool shade and bird song within reach. One could see the forest for the trees.

In 1972 Joseph Weitz, "the father of the forests," passed away. But the generations of foresters he had raised continued to follow in his footsteps and act on his vision, planting and caring for the country's new forests.

Apart from tending planted forests, KKL-JNF for the first time also turned its attention to looking after the country's natural woodlands. Nature clearly required some assistance. Long neglected, the scrub was overrun with weeds, and lower branches needed pruning to encourage proper growth.

Lahav Forest. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

The woodlands, since statehood, had been closed off to goatherds, notorious as Forestry Enemy Number One. Veteran foresters, like Tuvia Ashbel, were well aware of the talmudic warning " not to raise small cattle in the land of Israel" for goats and sheep destroy the green by climbing and overgrazing. But, suddenly, wardens began to find value in the controlled grazing of soft-toothed animals. Once a woodland had achieved the desired height, they brought in goats and allowed them to prune side branches and dense undergrowth, fashioning from each tree a "architectural exhibit" as Ashbel would say. As the goats turned from enemies into friends, the "jungle" of wild growth at dozens of woodlands throughout the country was thinned and opened to rainfall, which could finally penetrate the scrub. This resulted in the formation of a beneficial "forest floor" of organic nutrients that revived the natural woodlands and allowed them to flourish once more as they had done in First Temple, Second Temple, Mishnaic and Talmudic times. KKL-JNF restored the forests to their former glory, Ashbel said. It certainly restored more and more scenes and landscapes to Erez Israel.

The daring Weitz had shown in embarking on afforestation at Yatir was borne out again and again, at various locations. In 1971 the press reported on the successful afforestation of another dry, barren location, near Kibbutz Lahav in the south. Planted on the southern slopes of Mt. Hebron, the forest sprouted from rocky limestone in an area of little precipitation. The saplings acclimated better than anticipated and soon two million trees had altered the region's desert aspect, transforming another slice of Negev into forest.

A variegated forest was also planted n the former demilitarized zone of the Latrun enclave. According to the plan at the time, it was to extend along the old Green Line (the pre-1967 border), adorning the road from the foothills to Jerusalem in green and shade. The area, which had known bloody battles during the War of Independence and had later lain deserted and dismal, was now opened up by KKL-JNF bulldozers, followed closely by forestry workers.

Every forest created during those years – as 20,000 dunams were planted each year – added not only green but "green lungs" to the country. One Fund employee said at the time that KKL-JNF first "purchased the brown" (the soil) and then "restored the green." The "brown" work continued throughout, also in this decade, but with the intention of painting it green as soon as possible. The Information Department and Fund Director Jacob Tsur began to use a new terminology, then becoming common currency the world over: Ecology and, in the spirit of the times, with more and more talk of environmental quality, one of the Fund workers noted that KKL-JNF was becoming greener and greener, even when it worked with earth and dust – its goal being to transform the yellows and other shades of brown into the hues of buds and blossoms. In nature's spectrum, green is a blend of yellow and blue; at KKL-JNF, the entire gamut of colors, sometimes in defiance of the laws of nature but in the wake of hard work, resulted from the immediate contact between man and land.

Concomitant with forest care, for which landscape architects were now hired alongside foresters, KKL-JNF began to make its forests user-friendly, each year opening up another forest to the public. Trails were fixed and marked amid the trees, leading ramblers to enchanting spots of shade and serenity. As access improved, thousands of Israelis began to flock to forests and parks on weekends and holidays. This ingress into forests, which had been far from the eye and heart, changed Israel's leisure culture. KKL-JNF, it was said at the time, had taken a step towards the People whose donations had made forests possible, yet the forests, even those near big cities, had remained remote; few people were acquainted with them and hardly anyone ever entered them. Used to scorching landscapes of little shade, the public now discovered an enchanted, fairy-tale woodland world: Mushrooms sprouting up after the rain, birds returning to nest in symphonic serenade, wind rustling through the leaves and brooks of babbling water were all a powerful lodestone.

Ayalon-Canada Park. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

Ayalon-Canada Park, in the Judean foothills near Latrun, was opened to the public at that time. Hurshat Tal, at the foot of Mr. Hermon, was restored and became a National Park, attracting weekend excursionists and holiday-makers. Trails were blazed out to the top of Mt. Meron as well as a road between Sde Boker and the Ein Avdat spring and oasis. To acquaint the public with the sites, KKL-JNF's Information Department invited organizations and institutions (e.g., the Doctors Association, the Bar Association, the Engineers Association), on trips to forests that until then may have been points on the map and close to the heart, but outside the ken of most Israelis. To encourage the masses to flock to the forests, KKL-JNF began to install picnic tables and benches, fashioned from wood, of course.

The first bench was installed in 1972 at Menashe Forest near Kibbutz Hazore'a, prompting the press to dub KKL-JNF also a carpentry. "We still have not reached the number of tables and benches produced in Canadian, Finnish or Polish forests," noted Moshe Koller, Assistant Director of the Afforestation Department, "but at any rate we have reached the conclusion that it is not enough to plant trees for trees, after all, grow and need to be pruned (pines) or felled (eucalyptus). So the ball is now in the sawmill court…we threw out the challenge: To find ways to utilize the local lumber. This spawned the idea of producing equipment for 'active recreation' and creating a furniture style for picnic sites…" From that first bench, the Fund carpentry shop went on to turn out thousands more, as well as tables and other recreation equipment, making the forests more pleasant and convenient for visitors, virtually an outdoor "dining room" and meeting place, as one admiring journalist wrote; forests became more "human" and accessible.

"The simple fact of placing a table in a forest was an invitation to the public," said Theodor Hatalgi, who was in charge of publicity and led journalists on press tours in the hope that they would sing forests praises. Most of the newspapers during this decade began to run leisure, hiking and nature columns, for the first time introducing scenic spots that had been untrodden ground. The Information Department invited also foreign journalists, diplomats, and ambassadors to the forests, and Israeli landscapes – green spots in a desert land – received exposure in the international press as well. Despite their small dimensions, Israel's forests had made it onto the world map. Photographs of green plumage in a yellow Middle East excited not only diaspora Jewry who felt that they had shared in this color transformation, but also afforestation experts from huge evergreen forests, amazed by the refreshing change KKL-JNF had wrought on the land.

People who knew KKL-JNF, knew that the soil was its breath, the forests its air. This decade, however, was to ensure forests a prominent, striking place on the landscape. No more random or isolated patches of green here and there, but a planned, sculpted, invigorating green belt, impossible to ignore against the blinding eastern glare, just as it was impossible to ignore the fact that the whole of this green was entirely "blue-and-white."

To improve access to the new scenery and "green lungs," KKL-JNF built hundreds of kilometers of roads every year. Bulldozer blades bit into rock and stone, and, like artists or sculptors, fashioned both paved and unpaved routes on the landscape. The roads made it possible to draw nearer the stillness and, in the Negev – also to reach historical and archaeological sites that had been the preserve of agile hikers. Access roads were also built to Mt. Dov on the Hermon, and other border areas, where physical danger was imminent and palpable. In 1971, a worker in the north was injured when he stepped on a mine.

In 1973 KKL-JNF launched a long-term development plan to reclaim land, plant forests and build roads all over the country. A year later the Fund offices began to plan anew dozens of moshavim in the hilly regions – mostly in Galilee and the Judean Hills – to expand their economic base.

KKL-JNF, which in the 1950s had opened up and developed Jerusalem Corridor, as well as the Adullam and Taanach regions, in 1975 began to develop two new areas in Galilee: The Tefen and the Segev Blocs. Aimed at increasing the Jewish population in this area, settlement began as soon as land reclamation was finished. Like the three communities established in the Negev in 1943, the new communities were called mitzpim – outposts, because they were out of the way and hard to reach at the time. They were the brainchild of Meir Shamir whose posts included Director of the Fund's Land Development Authority, Deputy Director of the Jewish Agency's Settlement Department and head of the Israel Lands Administration.

To begin with, four outposts were established, each inhabited by a small number of families. It was a type of community that held out a strong attraction for many city-dwellers, especially the self-employed, who sought fresh air and liberation from urban traffic, noise, and pollution.

Wooden play facilities at KKL-JNF forests. KKL-JNF Photo Archive

KKL-JNF not only reclaimed the land, but returned to its time-honored role of previous decades: Land purchase. Fund representatives went from one Galilee village to another, buying up lands on which 29 new outposts had already arisen by the start of the next decade. Those who had thought land redemption a thing of the past saw the wheels of time restoring the Fund to the work it had done so well in the pre-state era. Some, familiar with Galilee's rocky, barren hills, viewed the communities as "mountaintop dreams" in the words of one newspaper. But the dreams very soon became real, greening the ground and painting roofs red.

In 1977, Jacob Tsur ended his term of office as head of KKL-JNF and Moshe Rivlin was appointed in his place, becoming the Fund's eighth Chairman and the first to have been born in the land of Israel.

In 1978, the Jewish Children's Forest was begun, to connect youngsters in Israel and abroad.

At the end of the 1970s, KKL-JNF took a good look at another part of the country –

the Besor region in the northwestern Negev. The area was slated for some of the communities of the Rafiah Salient, evacuated in the wake of the peace treaty with Egypt. Here, where the soil had seen neither investment nor irrigation for many years, one of the largest Negev settlement projects was to be carried out, this time for a Peace Salient (Pithat Shalom). KKL-JNF again harnessed its energies to state needs, preparing another broad area for new settlement.

In 1980, a year after the signing of the peace treaty with Egypt, the Fund's bulldozers "reconquered" the Negev as they prepared soil for Pithat Shalom. At the same time, new outposts were founded in Galilee and at Nahal Irron.

Speaking of these years, the driver of one of the bulldozers described how his caterpillar had raised huge clouds of dust into the air and developed new areas. Once the dust settled, however, one could see the many new square kilometers ready to be populated all over the country. "Keren Kayemeth," he said, "is everywhere… places we have worked at and will no doubt return to, for work nearby… I don't think there's a place that my bulldozer hasn't worked…" This man, who worked out in the field, saw himself as the direct descendant of the people who had toiled to drain the swamps or wielded the hoe in the 1950s. To him, the only difference was the advancing technology which allowed the Fund to do in the 1970s what had been impossible or more difficult 40 or 50 years earlier. The goal, however, had remained the same: To prepare land, be it rocky or arid, and transform it into another home, another field, another forest.